Should Two Edges Ever Meet?

The HEMAsphere is abuzz again with an oft-revisited discussion about whether sword parries should be done with the flat or the edge.

As I’ve covered before, parrying with the edge has historical precedent, biomechanical superiority, and provides stability in the blade. Yet two questions continue to come back to the fore and they’re worth addressing:

- Should parries ever be made edge-to-edge (i.e., at a 90-degree angle to the blow)?

- Would sharp-edged swords be able to withstand repeated edge-to-edge strikes without breaking?

Can Swords Handle It?

This second question is beginning to be explored by the excellent folks at Arms and Armor, who probably started this latest round of questioning with their recent YouTube video exploring edge-to-edge contact with live blades. Be sure to check it out here and give their video a like.

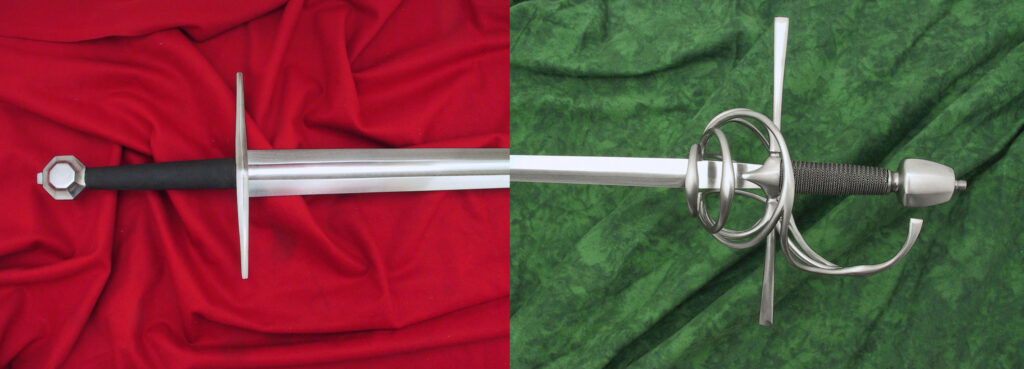

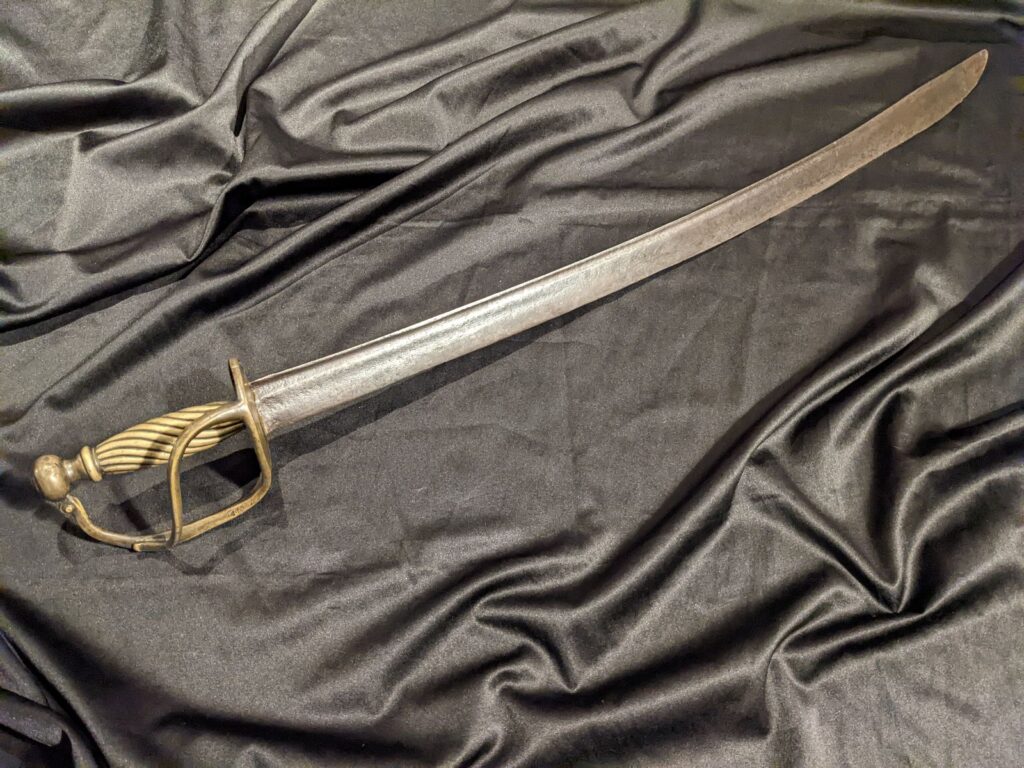

They’re going to need to release a few more videos to give us something more conclusive, but their start is really interesting. I have personally handled quite a number of museum pieces that have damaged or clearly repaired edges (indicating this kind of contact was made), including the 1700s-era Royal Artillery sabre in our own Academie Duello collection. A quality of most of these weapons is that many of them (two-handed and single-handed weapons alike) are not sharpened like a razor blade, nor are they sharpened to the same degree their entire lengths.

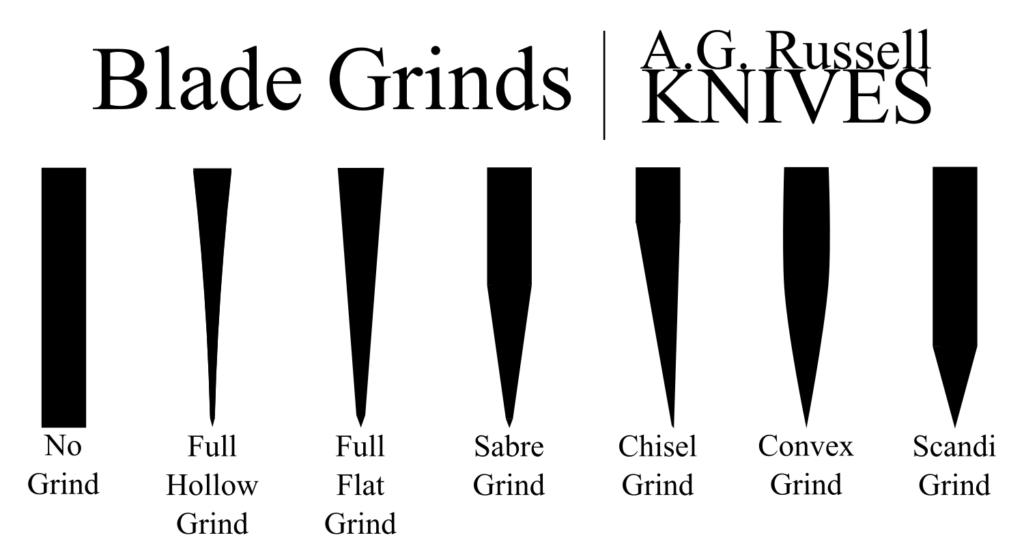

The finer the edge the easier the slice but also the more prone to damage (as you’ll see in the Arms and Armor video) and potential risk of breaking. This is especially true if the edge is struck in the same place multiple times. For this reason many European swords intended for battle were flat ground, sabre ground, or convex (how axes are typically sharpened). The reality is that a long bladed weapon can cut quite well even when its edge profile is more robust.

Check out this article from AG Russell Knives for a very nice tour of various edge grinds, how they’re achieved, and their pros and cons.

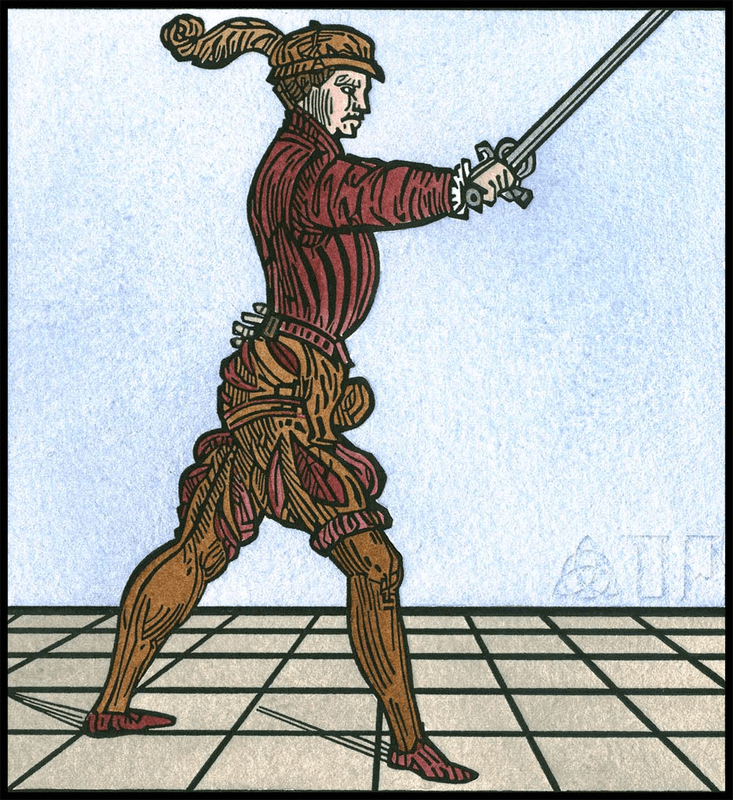

The edge profile of European swords frequently changes along the length of the blade, with the striking area being sharper and the parts used for parrying less sharp or even blunted. Many rapiers are finely sharpened only in their farthest extremes to aid with thrusting and cutting in the last 6–10 inches. The mid-section and lower part of the blade often remain unsharpened and progressively thicker.

This pattern, though often with a longer sharpened section, has been present in many historical longswords and arming swords I have handled as well. Being less sharp also facilitates gripping the blade, as is frequently shown and instructed in historical manuals.

Provided the edge is prepared for such things, blades can well handle edge-on-edge contact and historically frequently did.

Do You Want to Meet Edge-to-Edge?

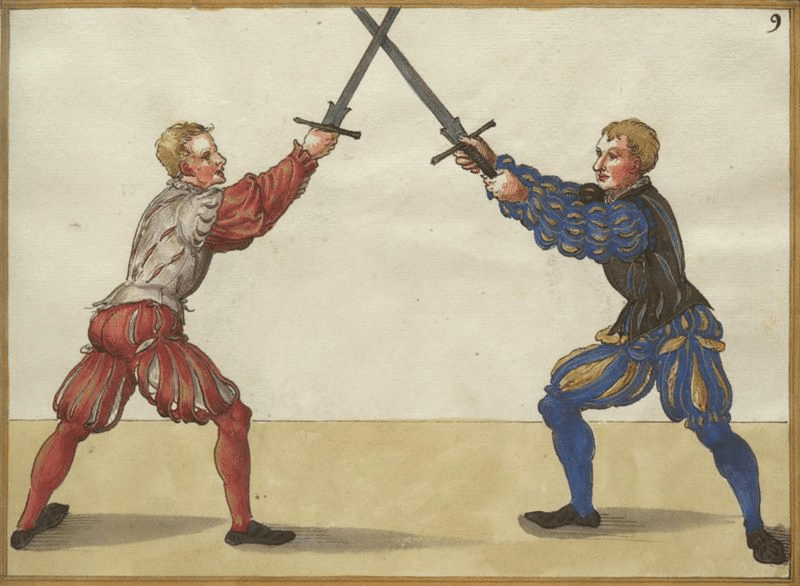

Typically when the topic of edge parries comes up many people jump into the discussion to share that you only ever want to parry with your edge to the opponent’s flat, or at an acute angle to the direction of their attack, so you don’t meet their edge at 90-degrees.

There are good many reasons to seek an edge-to-flat parry:

- When you strike into the flat or askew from the opponent’s edge all of the disadvantages of meeting with the flat are forced on the opponent.

- Sword crossbars are inline with the edge so when the edge is avoided it’s also easier to avoid being collected in the cross, leaving the opponent’s hands (and often the body) open.

- Whether they nick or not, sharp edges tend to bite and stick to one another. In cases of binds (where the edges are being pushed into one another) it can be harder for your sword to slide along the opponent’s weapon to strike a target.

- Direct 90-degree parries often leave fewer tactical counter-attack options open to you because they tend to place your point off target and fully arrest your sword in the making of the parry. Striking the flat or askew to the edge can allow you to counter-attack as part of your parry or quickly after.

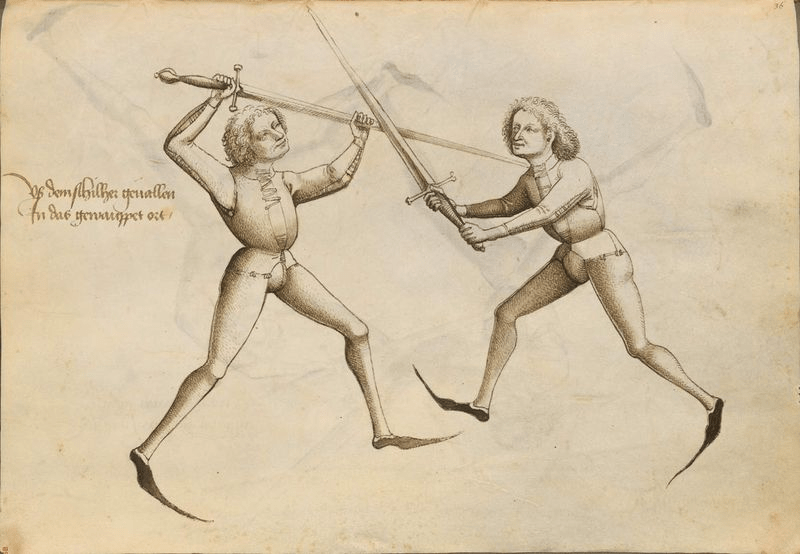

Even with this being the case, the circumstances that create edge-to-edge contact are frequent in European systems. Whether from placing the weapon directly into the path of an oncoming blow or in circumstances where an opponent deliberately seeks to bind (typically, seeing your defense they turn their attack directly into your sword to avoid being displaced).

More direct blocking actions, like Marozzo’s guardia di testa, are often sought because they provide a more complete cover while maintaining the structural integrity of edge alignment. Direct blade meetings can also be used to arrest the opponent’s sword, specifically seeking to keep it present and not deflect it away. Edge-to-edge contact is also sought specifically to prevent the opponent from meeting your flat, defending you from the disadvantages described above.

Though an edge-to-flat meeting might be optimal in many circumstances, it is not always desired nor always possible.

A Deeper Dive

If you’re interested in a well-researched exploration of why the edge is the primary parrying surface in European swordplay check out this thorough article by Andrea Morini from 2012. He also explores some of the exceptions that prove the rule, such as the flat parry pictured at the top of his article.

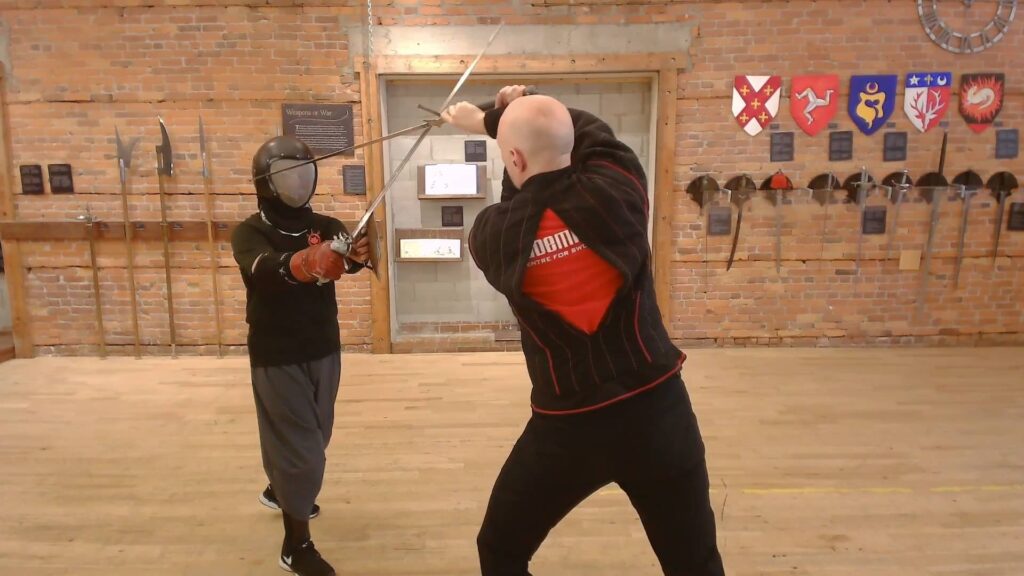

I also encourage you to test these ideas out for yourself. Many of the advantages and disadvantages of edge- and flat-parrying as described in the Morini article can be easily explored with blunt trainers and appropriate protective equipment. As with many arguments some are perhaps best settled with swords — though leave the sharps testing to our friends at Arms and Armor!