Learn the Language of Ancient Fight Books

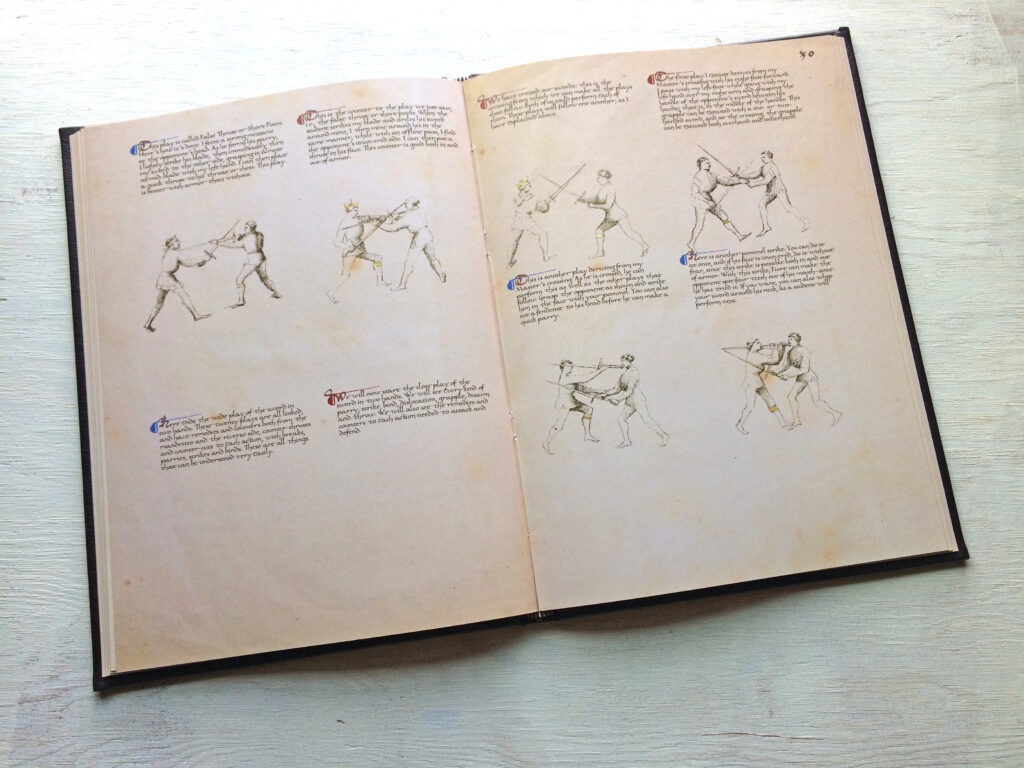

One of the most interesting things about Historical European Martial Arts is that original teachings of masters from the 14th to 17th centuries are available to us as students and practitioners to read. One of the challenges is that these old fight books are usually written in languages you don’t know and using conventions you might not be familiar with.

As a modern practitioner you have two choices:

- Find good English translations of those books.

- Start learning another language.

Fortunately there are many great translations of historical fight books available these days, but even with that, I have found that one of the most powerful ways to connect with an ancient martial culture is to access it in its native language. When you are doing your own interpretive work from primary sources, it can also be useful to be able to investigate modern translations more thoroughly by better understanding the interpretive choices that the translator has made.

So today, I want to share with you some useful resources, tips, and guidance that I have found helpful in my journey in connecting with historical fight books.

Start with the Modern Language

The first language I wanted to learn was Italian. It’s the language of Fiore dei Liberi, Antonio Manciolino, Salvator Fabris, and so many more historical masters of the early and late Renaissance.

One of the biggest mistakes I made at the start was to shun modern learning sources, thinking that the 400-year-old version of Italian was too distinct from modern Italian to make it worthwhile.

Though most texts are written in older versions of the languages, in the case of both German and the Romance languages (Italian, French, Spanish), the historical language and modern language are still quite similar in structure and vocabulary—at least enough to be the best starting point for learning. English has actually undergone a much more significant shift in its vocabulary and written form over the last 500 years than those others.

Modern learning resources are a great first starting point as there are many very well structured programs available online.

Language Learning Online

There are four services that I have used online to learn other languages. Each is useful when used in its right place.

Duolingo

The world’s most popular language learning resource (mostly because there is a free version) offers a gamified language learning model. It has courses for hundreds of languages useful for learning martial arts, including Klingon. Daily lessons and challenges, rewards and games, all make the learning process fun and bite sized.

I am a subscriber to Duolingo and have used it for French, Italian, and Chinese.

I have found Duolingo to be a great tool for getting initial exposure to a language and for helping to create a simple and maintainable daily practice. It will not get you writing or speaking in your target language on its own, but it will keep you connected and help you expand and maintain your vocabulary. It’s also a super easy way to get started. I recommend downloading the app right away and giving it a shot for free.

Mango Languages

I have used Mango for learning Spanish. It has some similarities to Duolingo in its use of flashcard style testing and learning, but it also offers more structure language lessons on grammar, verb conjugation, and general language structure. It also has some great tools for pronunciation and a lot of additional language resources such as verb charts. It is a subscription service only.

iTalki

This service connects learners with teachers for 1-on-1 online lessons, to group lessons, and to other language learners to do speaking trades (e.g. I am an English speaker learning Italian. You are an Italian speaker learning English. Let’s get together and talk for an hour where we spend 30 minutes in your target language and 30 minutes in mine helping each other learn.)

When I decided I wanted to up my spoken Italian game this app was a game changer. Weekly speaking sessions, combined with daily Duolingo practice, helped me start thinking in the language and move from word-by-word translation into more natural speech. You can chat and look at screen shares to add to the writing/reading side of the experience.

iTalki ended up being the inspiration for setting up weekly Zoom calls with one of my students in Italy who was invaluable for helping me really build my Italian fluency—thanks Giuseppe!

ChatGPT

AI is already being integrated into services like Duolingo to help with language learning, but why not go to the source. I use ChatGPT in three different ways:

- Understanding questions in Duolingo I got wrong. You can literally take a screenshot of a Duolingo question you got wrong and upload it to ChatGPT and ask “Help me understand what I got wrong.” and it will give you a helpful breakdown based on what it sees.

- Talking to me in Italian to help me practice. Both through text chatting and through the advanced voice feature (available to subscribers) I simply prompt ChatGPT to be an Italian tutor to help me with conversational Italian. You can control the amount you want to speak in your target language, topics you’d like to discuss, or weak areas of grammar you want to develop. You can even ask it to talk to you about historical fencing or help you build your capacity to read historical texts.

- Translating historical texts. I use a lot of different resources to help me find the meanings of words and phrases in historical manuals, wordreference.com being a major one, but ChatGPT has impressed me with its ability to connect me with the meanings of ancient words and turns of phrase. Always be aware of hallucinations and check other sources to back up your findings when certainty is important.

Use Cognates to Build your Vocabulary

The Internet is also a great place to find lists of cognates and loan words between your target language and English, like this one of 125 English and Italian Cognates. Cognates are words that have a common origin between the two languages, like the Italian “abilità” and the English “ability”. Loan words have been directly borrowed by one language from the other typically to describe newly introduced things or concepts. A good example being the French word “croissant” that was loaned to English, along with the pastry it describes, from French.

These matching words can give you a big head start in establishing an initial vocabulary. There are many Italian/English cognates that show up in historical fencing texts, a few examples:

- Parare – the Italian verb “to parry”

- Punta – the Italian word for “point”

- Contrario – the Italian word for “counter”

- Contra-postura – Italian for “counter-posture”

There are also likely many related words that are not quite cognates but will still help you in learning the new language. The Italian word “misura” used in fencing to refer to the distance between you and your opponent (and the judgment of that distance) is related to the English word “measure”, both share the same Latin root: mensura. This word is also connected to the German term “mensur” and “mensuren” terms used to signify both the distances between fighters in a ritualized duel and the name of that duelling form itself.

Nearly 70% of English vocabulary is borrowed from other languages. This means if you are a fluent English speaker you have a great head start in your learning across dozens of other languages many of which are used in primary historical fencing sources.

Leverage Online Community

iTalki is one way you can connect with a language learning buddy, but the world of Historical European Martial Arts is full of people interested to connect with others. Put the word out onto an international forum like the HEMA International Discussion group on Facebook to find others interested in doing a language trade with you.

Online forums are also a great place to get help with words and phrases you’re having a hard time with. HEMA forums frequently have many other amateur translators willing to share their thoughts. Reddit is also full of language forums for learning basically any language you’re interested in. I have found tons of useful help just by reading through the posts on r/Italianlearning.

Decoding Letters

One big challenge when working with an original source is that not only is it in a foreign language but it can also be difficult to decode the writing itself.

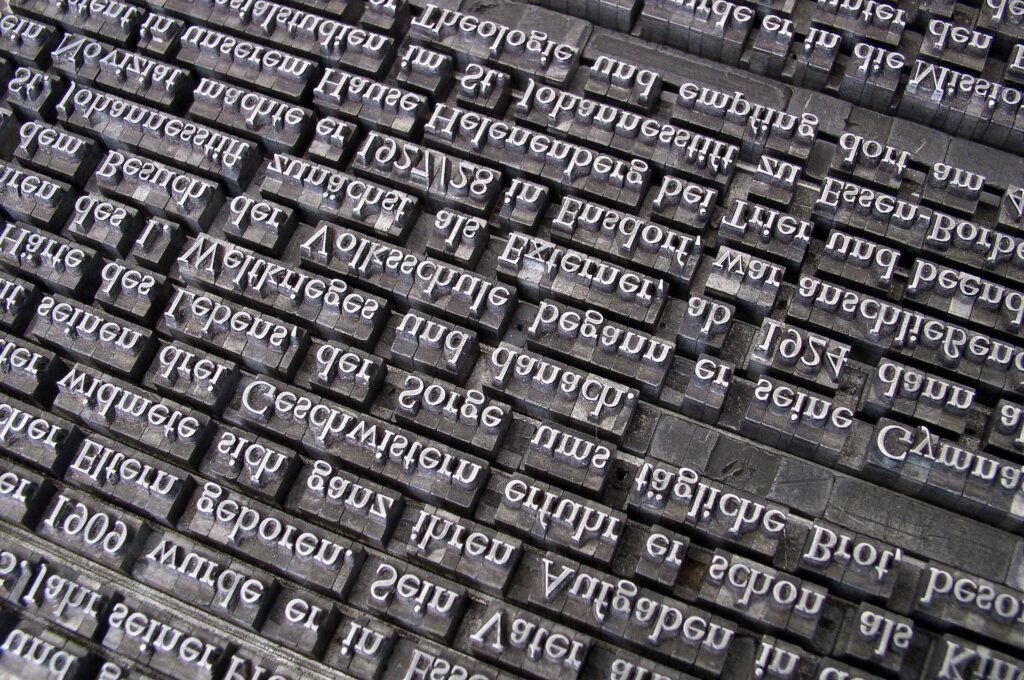

Manuscripts (hand written) are often written in stylized scripts that can be hard to understand and printed books use orthographic and typographic conventions not familiar to modern readers.

Some examples of these include:

- The long “s”. This character often used at the beginning and middle of words looks like an “f” without a full crossbar.

- “u” and “v” confusion. These letters are often used interchangeably.

- “i” and “j” confusion. These two letters were not distinct from each other until the 16th and 17th centuries. Many texts use the “i” for both the vowel and consonant.

- Ligatures and shortened words. There are many places in fight books where you’ll find two or more letters joined together into a single character such as when “paſta” stands in for “passata”. It’s common for the letter “n” following a vowel to be rendered as a tilde above the vowel as in “mão” instead of “mano”, the Italian word for hand. There are dozens of other similar shortenings you need to be on the lookout for.

- Double letters. In some German fight books you’ll find the word “vvinnen” instead of the more modern “winden” for “winding” (an action of twisting your sword against your opponent’s). “W” was often rendered as two u or v characters.

- The ampersand (&). In some texts this appears more explicitly as a stylized “et” with the two characters connecting together. “Et” is the latin word for “and”.

One of the best ways to deal with these challenges is to find a good modern transcription of the original text. Wiktenauer, which also has many translations, is also a great source for transcriptions of historical manuals. Be aware that some transcriptions I have found have incorrectly transcribed these confusions leading to a document full of the word “paffata”.

Old Language, Idioms, and Jargon

Another challenge when reading and translating historical texts is that some bits of the language are jargon, idioms, or dialectic words that have fallen out of usage or are still used but only in very specific regions. The Italian word “stramazzone” (a circular cut delivered from the wrist), for example, is unknown to modern speakers and even has a few conflicting historical definitions.

I have found that ChatGPT can help spot and decode some of these (ask it to give sources and references to other reading that you can follow up on to verify its claims). The best approach is to connect with knowledgeable native speakers and translators while also building your knowledge of contemporary writing and history. Wordreference.com (at least for the latin languages) gives a fair bit of etymological sources that can be helpful for investigating some old technical jargon.

Remember as well that the spelling may have changed or you may be misreading it based on some of the typographic and orthographic changes detailed above.

In some cases I have found using contemporary translation dictionaries to be helpful, such as Florio’s New World of Word’s published in 1611, that details translations between Italian and English. However, at least in this case, I have often found that Florio got it wrong and finding modern etymological references has been more useful.

Set a Rhythm

Like your martial arts practice, the best thing to do is to get into a daily or weekly rhythm. I have found that a weekly speaking date and a daily Duolingo practice has been both sustainable and has given me real forward progress.

It’s important to find a rhythm and process that works for you and is engaging and enjoyable.

Have a Project

Having a fun project to work on makes learning a language far more motivating and interesting. There’s really no reason to not start on a reading or translating project right away. You can do a lot with Google Translate, Word Reference, and ChatGPT.

I like to use a spreadsheet program like Excel or Google sheets to place transcribed passages alongside my translation in manageable chunks.

It can also be useful to do this same process alongside an existing translation. You can then compare your work to the other translation and use the differences as a jumping off point for further investigation and learning.

One nice thing about fencing texts is that they use a lot of technical jargon you’re probably already familiar with and they tend to be more focused on repeated technical descriptions rather than flowery prose.

Start Talking

The best thing you can do to learn a new language is to start using it—badly. Beyond all the online and community resources I’ve listed above, getting involved in a regular speaking group was really helpful for me. You can find in-person language groups in your area through services like meetup.com and through local cultural centers. You’ll find that having an interest in something like sword fighting manuals will make you a hit in your group and give you a great jumping off point for many conversations.

Share Your Experiences with Me

Have you found useful resources in your language learning journey? Share them with me and I’ll add them to this post in future updates!

I hope that you are inspired to start on your language learning journey!