An Argument for Training with Diverse Weapons, Part 1

Recently I was asked why we teach rapier and longsword together in our Instructor Intensives. The questioner postulated that it was like teaching sky diving and skin diving in the same program. Sure rapiers and longswords are both swords but aren’t they as distinct as these two types of “diving”? I think it’s a great question. I’d like to answer it in a few parts across multiple posts.

First, what is the historical precedent for teaching the rapier and longsword together, and for multi-disciplinary approaches in general? Second, how different are the rapier and longsword and what can the lessons from one offer the other? Third, what if they are supremely distinct, does that matter? Is their value in the study of disparate disciplines in parallel to one another? So let’s take our first dive into these questions.

The Historical Precedent

Nowadays in the world or Historical European Martial Arts it is not uncommon to meet many practitioners who practice only longsword, or only rapier, or only sabre. Or, even if they are multi-weapon practitioners, they will study distinct and disparate approaches to each weapon where the study, methods, and language are all distinct from one another.

A single weapon focus is certainly much simpler from a first learning perspective. If the weapons are seen as being completely distinct in nature, and a different set of terms and language is used to describe their actions, this is going to be overwhelming for anyone but the most experienced of practitioners.

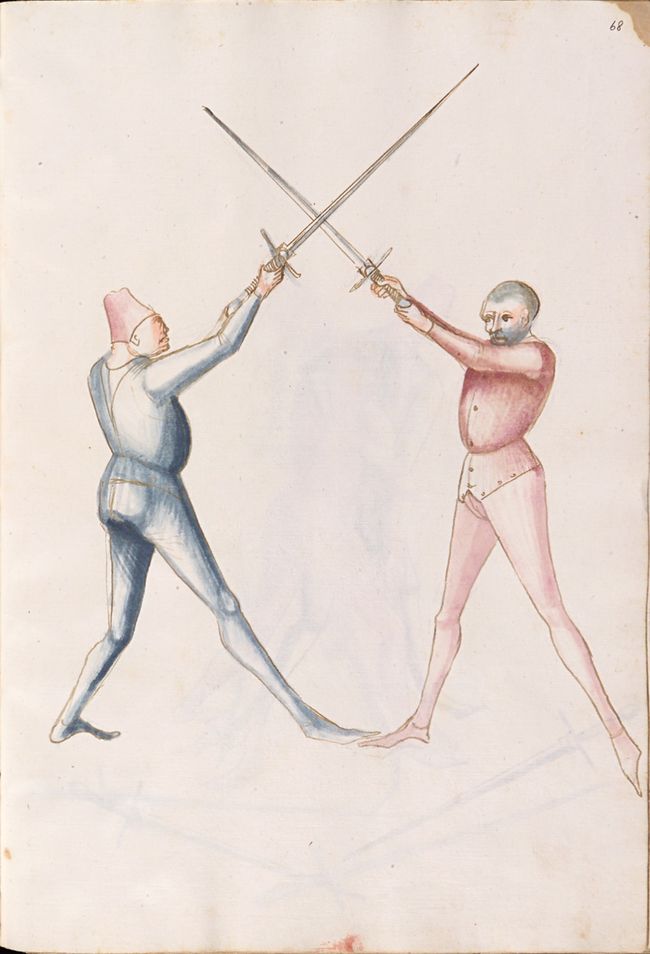

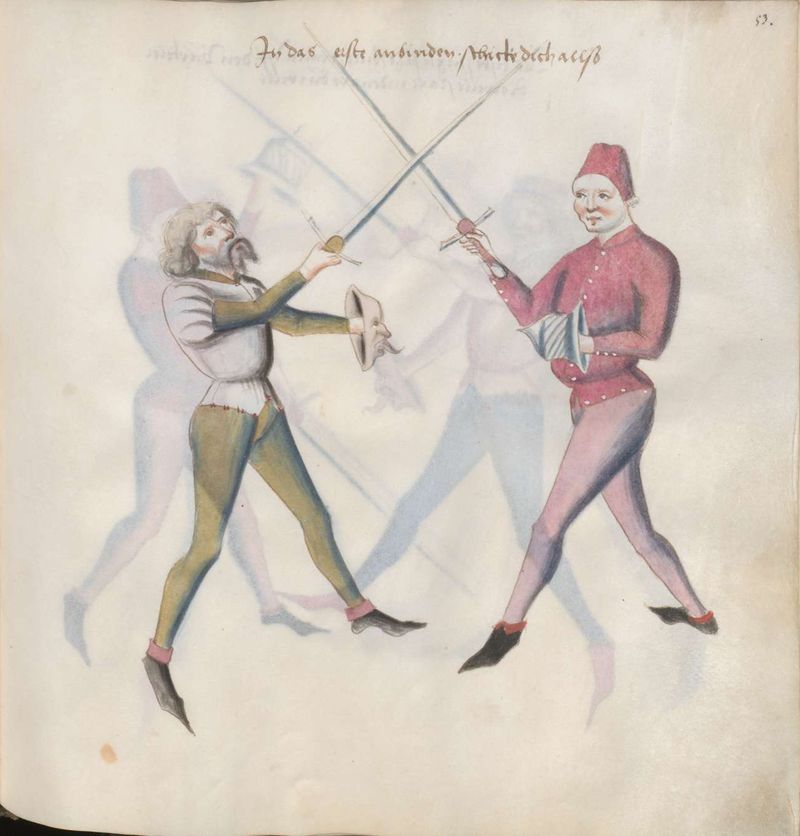

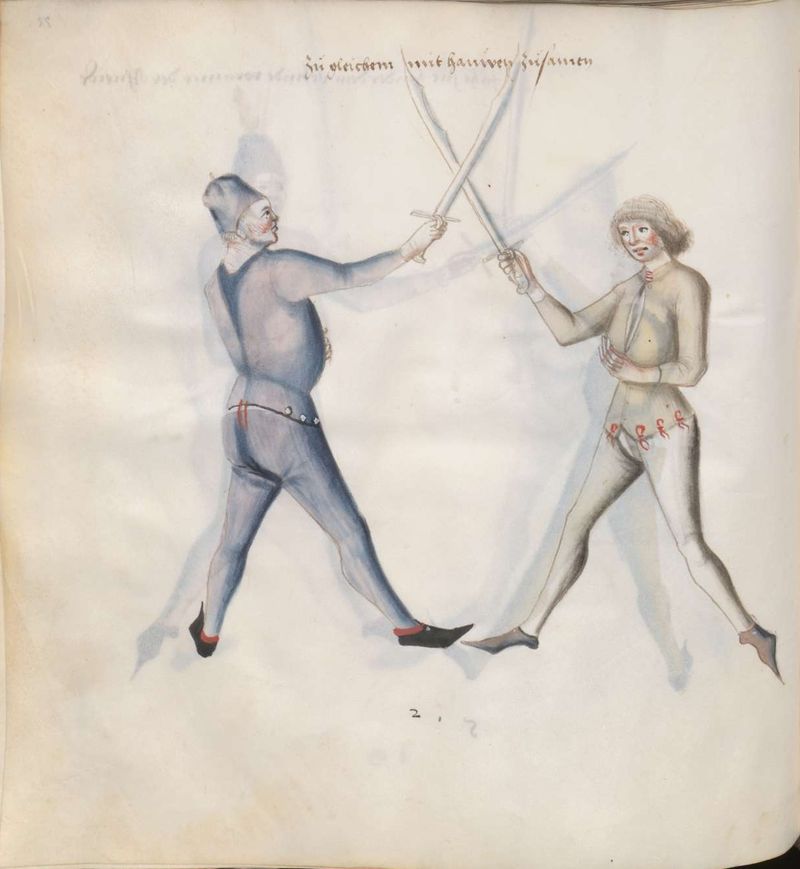

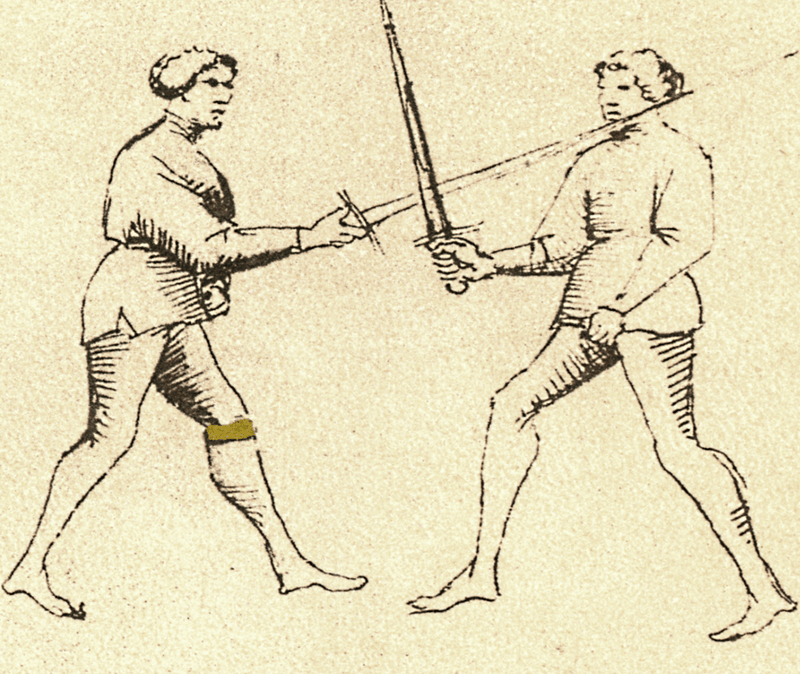

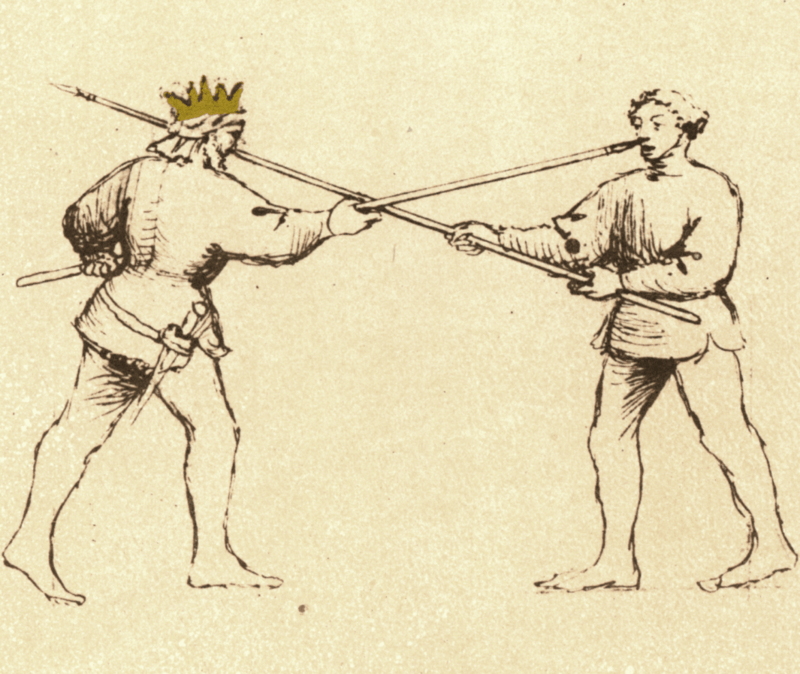

Yet, when we look back to the written roots of European Martial Arts, in the middle ages, we see a common presentation of multi-weapon systems of combat.

These masters present a unified martial art where, whatever the tool in-hand, their art prescribed a common strategic, tactical, and bio-mechanical approach. Each weapon and context necessarily directs that approach, bringing certain principles more greatly to the fore, but in many ways it is the universality of their art that makes it most useful.

You never know what constraints might be in place when the need for martial resolution arises. You do not know what type of ground you might be on, what types of weapons you might be facing, what weapons you will have at hand, or what constraints might be placed by the court (in the case of judicial dueling). The more flexible and diverse your art the more easily applied it will be and the more easily your science will be able to describe and understand the art of an unfamiliar opponent or armament.

Renaissance Italy

This universality of approach holds well into the Renaissance, and this is where we first see various types of rapiers in the broader systems of historical masters.

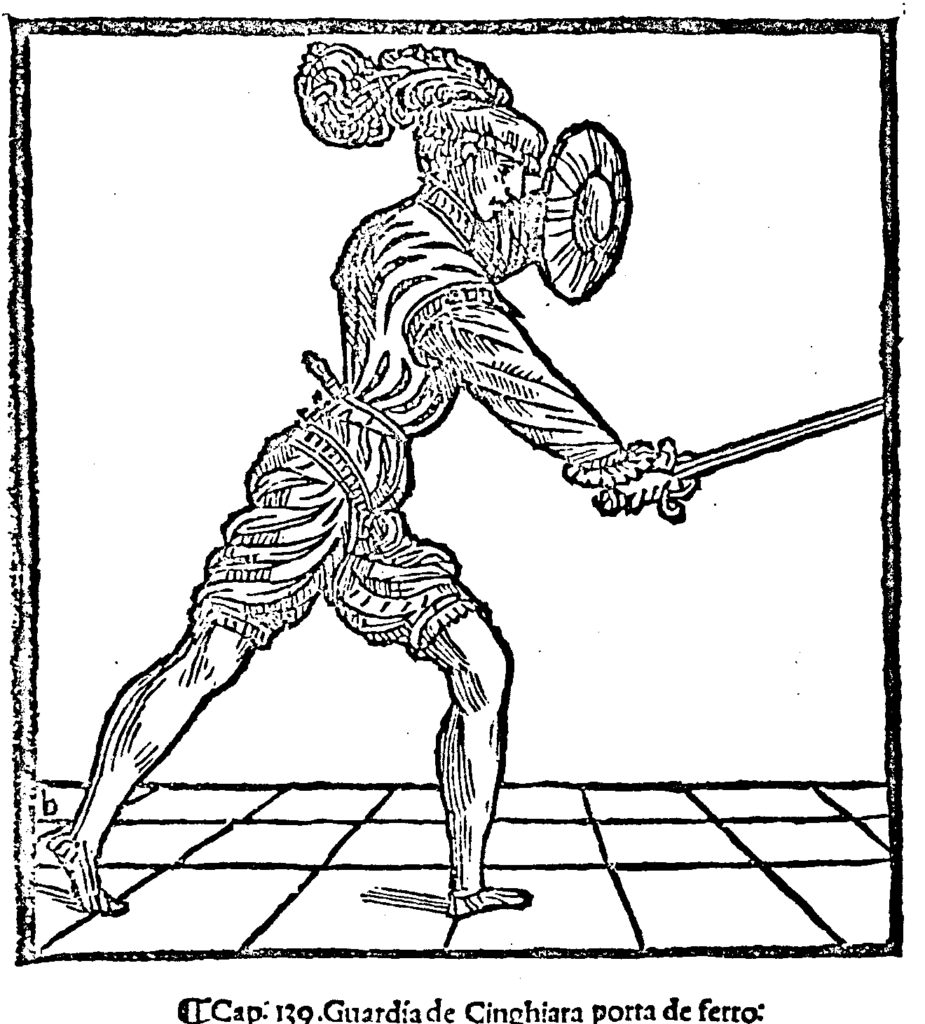

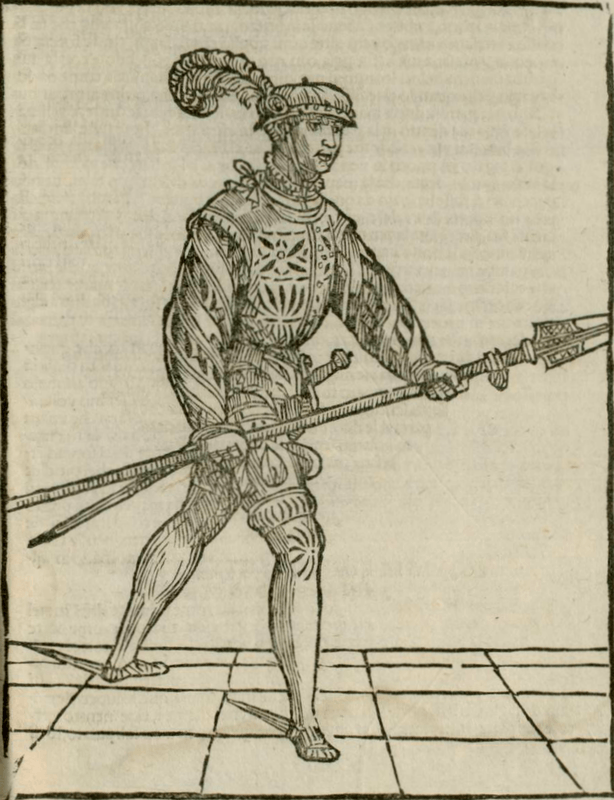

All of the Bolognese Masters (Achille Marozzo, Antonio Manciolino, Dall’Aggochie, and the Anonymous) include a diverse array of weapons in their systems including the rapier (which we might now call a sidesword), polearms, and two-handed swords

The weapons they employ use the same guards (with some variations between weapons), manoeuvres (such as stramazonne, mezza volta, thrusts, and various cuts), application of leverage, and most important, the same strategic and tactical thinking.

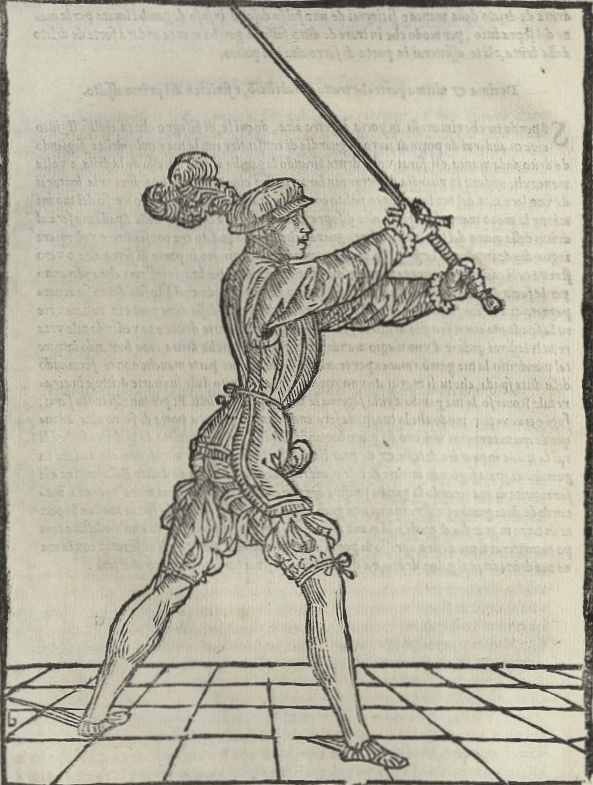

Germany and Elsewhere

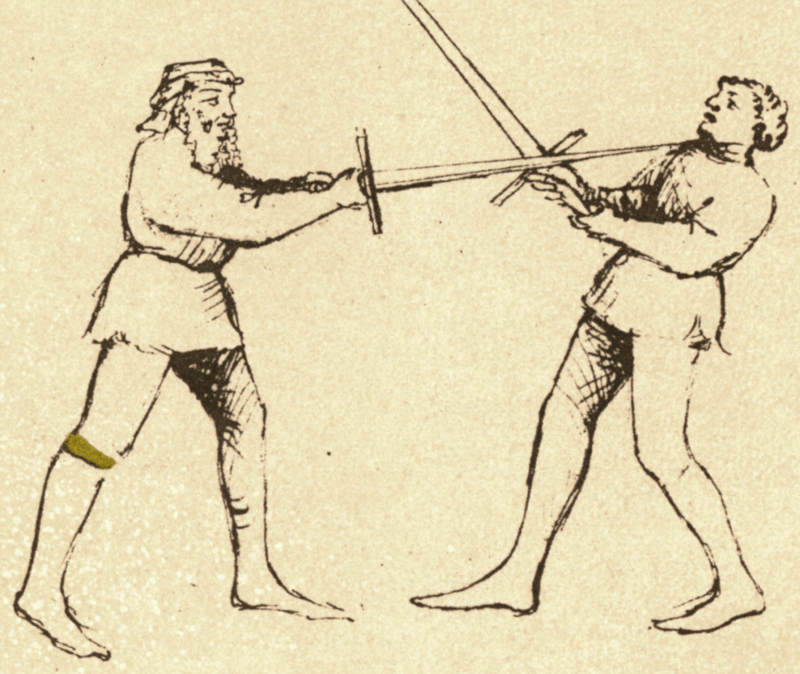

The same is true of Joachim Meyer who wrote at least three manuals between 1560 and 1570 in Germany. Meyer brings the early rapier into a system that includes the two-handed sword, dussack, dagger, and polearms. Interestingly at the end of the rapier system Joachim tells his readers to use the rapier, and all weapons, in the same manner: extended with the point directed at the opponent (“extended, straight, and firm parrying”). Here is the full text:

When find yourself in rapier combat or any other weapon, then approach him with extended, straight, and firm parrying, and take heed what he will execute against you and from which side he will cut or thrust in. From whichever side he sends in his cut, catch and parry his cut, and cut or thrust in at him to the same side from which he has sent in his cut, before he has entirely finished it, or at least before he has recovered from it again.

Joachim Meyer, 1570, 2.98v

This universality persists throughout writing in Western Europe even as the practical battlefield, or self-defense use, of multiple weapons diminishes. La Verdadera Destreza was an art and science of fencing developed within the Iberian peninsula that focused primarily on the rapier but was applied to a diversity of weapons, by its many adherents, that included polearms, flail, and montante (a large two-handed sword). Destreza was intended as a universal method that could be applied to any armament or context. It was also seen more broadly as a way to learn and practice a broader set of humanist ideals.

In Conclusion

We can see in these texts that there is a practical need for multi-disciplinary practice in the time of these authours; the capacity to be able to pick up any weapon at hand, even an unfamiliar one, and understand how to use it effectively, and the capacity to be able to understand and counter an unfamiliar weapon or approach.

There is also a pedagogical and practice payoff. When there is a requirement in your martial life to use and be proficient with multiple weapons, having a unified approach to their use means that all of your practice time is relevant, regardless of which weapon you’re training with in the moment. It also allows a teacher to reinforce and expand a student’s understanding of given principles, tactical and physical, by demonstrating them across disciplines.

The lessons that a particular master wanted us to glean from one weapon and apply to another is not always as clear as Meyer’s advice in his section on the rapier, but through inter-disciplinary study the commonalities can certainly become clear to you. In part 2 of this series I’ll explore the connections between the longsword and rapier specifically, and why I think they’re excellent cross-training companions.

Devon,

Very good article. As you know, my Salle, Salle Marquis de Lafayette, here in New Jersey is an affiliate school of Academie Duello. We hold that title of great value and as I’m sure you will recall the very reason I sought such affiliation was your seemless pedagogy. In AD’s approach to teaching there is focus on how all the weapons are more the same then they are different. In short, it is the essence of “Schema” (to defend oneself) which is where the original word for “Escrime” is derived.

Indeed, beyond the examples you’ve given thus far there are many which deal with effectively engaging against weapons of another type than the one with which you are armed. Understanding the strength of each weapon will also bring to light any inherent vulnerabilities.

Having served in the Military I was trained to not only in the use of the issued hand held weapons of my own service but also that of any adversary I might likely face. We must remember this is a martial art and we must be able to take on all comers.

Again, very well done and very informative.

Hi Tom, thanks for the response. I think the military link is a really good one to bring up, considering that both historical and modern militaries recognized this need for multi-disciplinary practice.

Great article! I’ve thought about this and how it would be nice to not only know how to use one kind of sword but to know how to use others as well.

All training is good training, Brittany, and if you can learn from principle then you can apply principles from one weapon to another. All your swordplay principles taught in AD’s system will transfer from one weapon to another.