Spadone: Swinging Big Swords

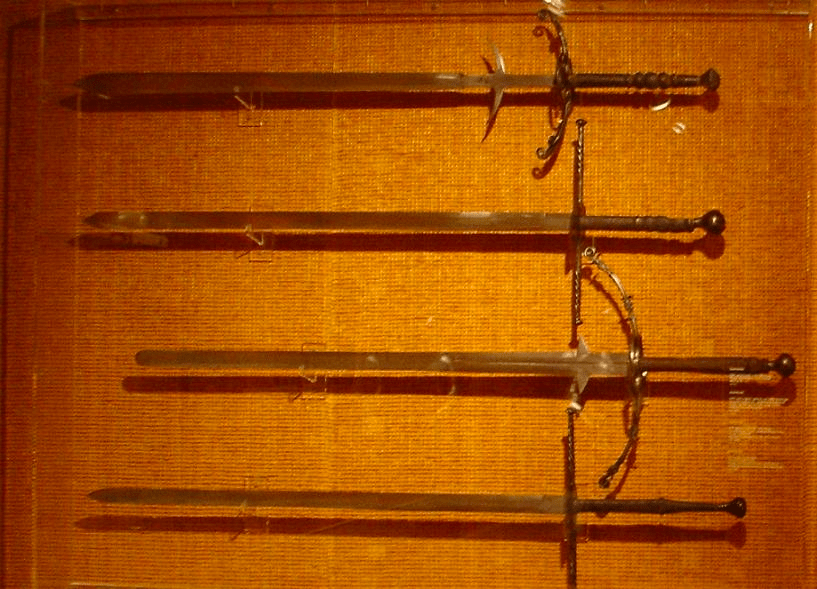

Greatswords (spadone in Italian) are a class of two-handed swords that tended to be longer and heavier than your typical medieval longsword. They had longer blades, handles, and quillons, as well as sporting additional features such as ricasso quillons — two short spikes a handspan or two from the crossbar.

Most were typically about 4.5 feet long and between 4 and 5 pounds though I have handled some museum swords that fit this bill that were both lighter and heavier. They were meant to be wielded in two hands and favored power over the flexibility of the middle ages longswords that preceded them.

Lo Spadone

The term greatsword is a relatively modern term that is used as a catch all for a variety of terms used historically and in modern times including the Italian Spadone, Spanish Montante, and German Zweihänder.

Achille Marozzo is the first Italian to be writing about a weapon that fit the characteristics of a greatsword in 1536 but he simply called the weapon a Spada a Due Mani (a two-handed sword). A later master, Francesco Alfieri used the term Spadone (greatsword) in his 1653 work.

I personally favour the term spadone to help contrast it from the shorter medieval longsword of Fiore and even the slightly longer one described by Filippo Vadi.

Why Swing Big Swords?

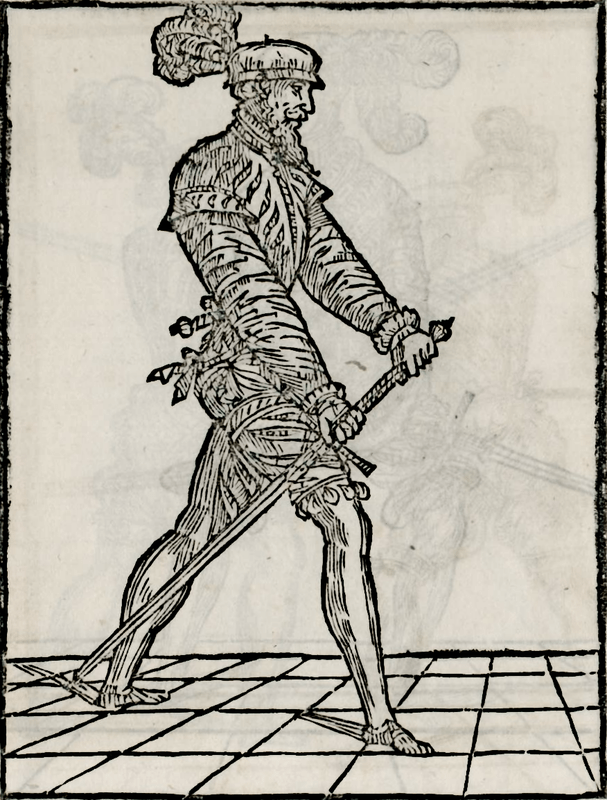

Historically greatswords were used by specialized soldiers, often who acted as skirmishers against pike units where their swords could act as short spears or be used to harass the points of the pikes and create opportunities to enter and break the unit. They were also used by civil defense units to control crowds, guard the entries to squares, and even fight in corridors as the manual of Diogo Gomes de Figueiredo describes.

Beyond these specialized uses, greatswords existed in a time when swords were finding their way off of battlefields, replaced by pikes, powerful bows, and guns. Where they did continue to find a place for practice was for fitness, performance, and to prepare the body for using other more common weapons.

“The exercise of the Spadone is to be commended in that it readies the feet, makes the body flexible, helps the hands acquire strength, and loosens the arms.” so says Alfieri in his introduction.

There are several descriptions of martial displays being done with the spadone in the 1500s and Marozzo’s instruction for the weapon is provided almost exclusively in the form of three partnered martial forms (assaults) that move through the techniques in a choreographed pattern of attacks, defenses, and embellishments.

Having the capacity to swing around a big sword with ease could translate well to all other manner of encounters with lighter swords as well as other similar weapons like long staffs and halberds. It was also seen as a very “manly” way to stay in shape.

Modern Practice of the Spadone

The Spadone plays a similar fitness role in modern Duello Armizare. Swinging around a big sword teaches you a lot about how to use your whole body in the cut as well as how to work with the momentum and inertia of a weapon. If you don’t relax and engage in just the right ways the mass of the spadone really lets you know when you’re not moving in sync with the weapon.

I have found that a short period of using the spadone will improve someone’s cutting with the sidesword and longsword significantly while being a fun and engaging weapon in its own right.

Even if you don’t have a giant sword of your own you can get a lot out of studying the forms and positions of the spadone with a shorter longsword or a DIY wooden stand-in.

Cover image courtesy of Balefire Blades, The Trelati Spadone