A Deep Dive Into Disarms

Disarms, or “sword takings” (prese della spada) as they’re typically called in Italian martial arts, are not just the cool fodder of movie sword fights. They are an important part of martial traditions from around the world, including those from Europe, and to get good at them requires that you develop exceptional timing, dexterity, and an intimate understanding of body mechanics.

When to Disarm

Disarms are relatively complex and often place you closer to an opponent’s weapon, into a position of potential struggle, and put your extremities at risk. In many situations where you could conduct a disarm it might be easier, and more final, to simply strike the opponent. So why ever do one?

Though modern sporting competition often puts a priority on striking high point-scoring targets, the contexts for martial arts are more complex and varied. Disarms in most European traditions are applied in four main contexts:

- Neutralizing a threat in a context where you don’t want to kill or injure your opponent. There are many subduing techniques in European traditions because, like now, it is often illegal or impolitic to kill someone. Europe in the late meddle ages and renaissance was certainly more violent but it was still a place of laws and even in environments that were beyond laws, willy-nilly killing still had consequences. In our school we sometimes do drills I call “drunken cousin” exercises. The scenario being that one person is your drunken cousin who is enraged and violent. He doesn’t care in that moment about injuring you, but you have to disarm him without harm.

- Controlling a weapon so it can’t strike twice. There are many historical accounts of duels where one or both participants were struck multiple times. Being able to disarm or grab hold of an enemy weapon while or after you strike can ensure that even an injured opponent is less dangerous. In the Spanish rapier tradition “movements of conclusion” are described where the hilt of the opponent’s weapon is seized during an entering action. The opponent can then be dealt with more safely or forced to yield.

- Display of skill. Whether in a duel or public display, a component of fencing in Italian traditions in particular is showing off your valour and skill. Taking an opponent’s weapon from them does both.

- A follow-up when an attack fails. Fiore dei Liberi in his early 15th century treatise describes a disarm that follows a failure to wound. “…the Scholar who came before me did not immediately thrust his point into the face of the player, or he failed such that he could not thrust into his face nor into his chest, or that the opponent was armored, then immediately the Scholar should step with his left foot forward, and he should make a grip in this manner.”

How to Disarm

There are five components to a successful disarm:

1. Commitment from the opponent – Disarms need a committed attack or a commitment to struggle and push into a crossing (or both). Typically you need to lure an opponent to believe they’ve got you so they make a large motion with a lot of extension.

2. Timing – When you have commitment you still need to be ready to capture the moment. You must have seized or begun to apply your lever near or at the end of their attacking action and no later. Disarms fail when you chase after an opponent who is already into the motion of recovery or redoubling.

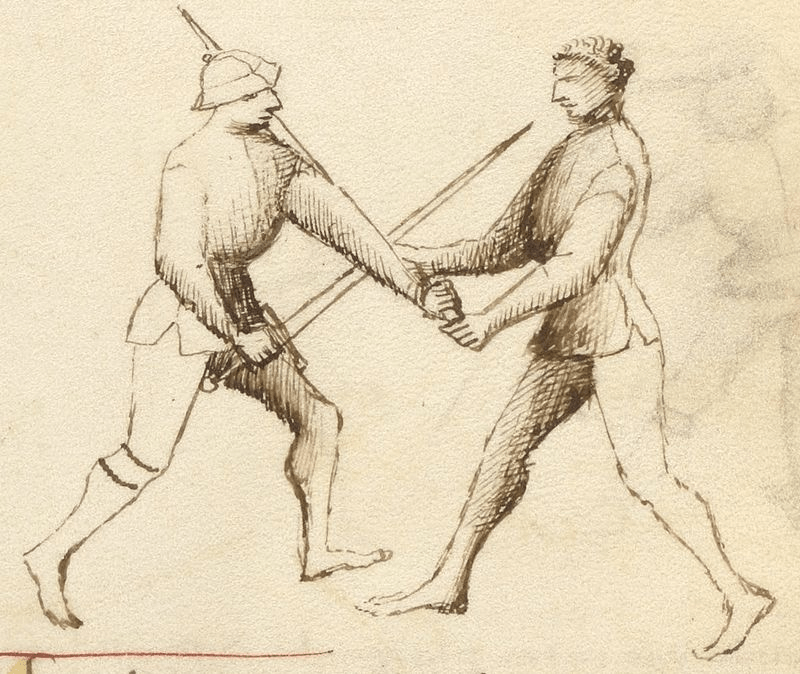

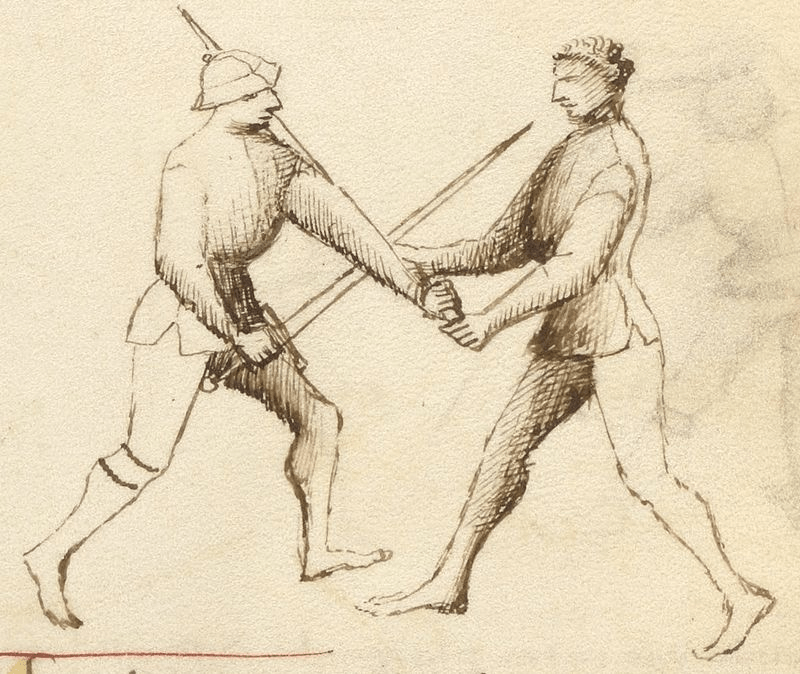

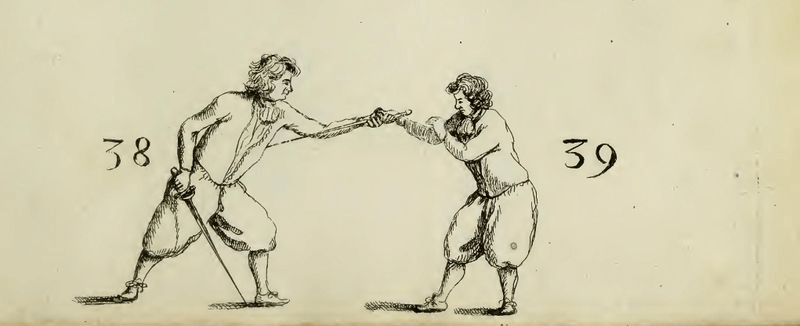

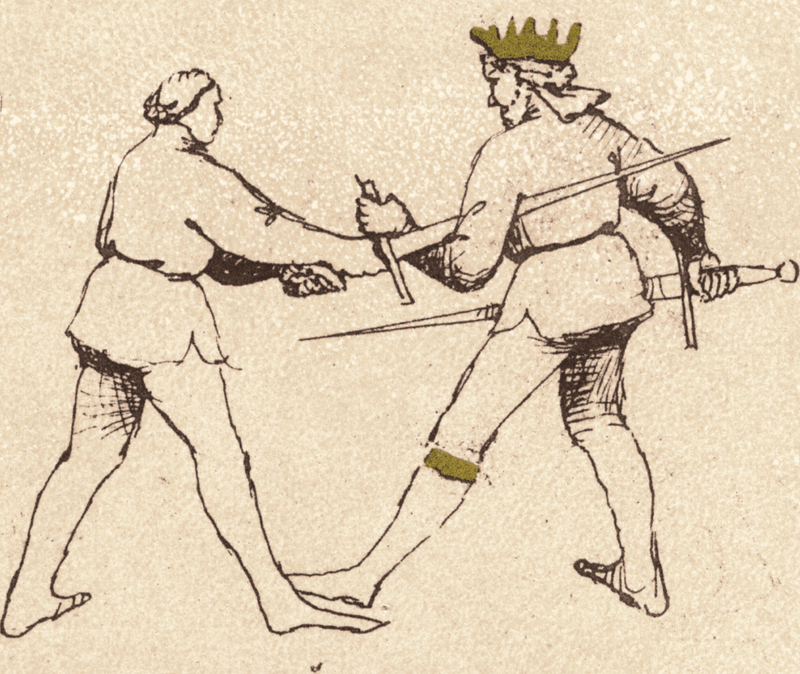

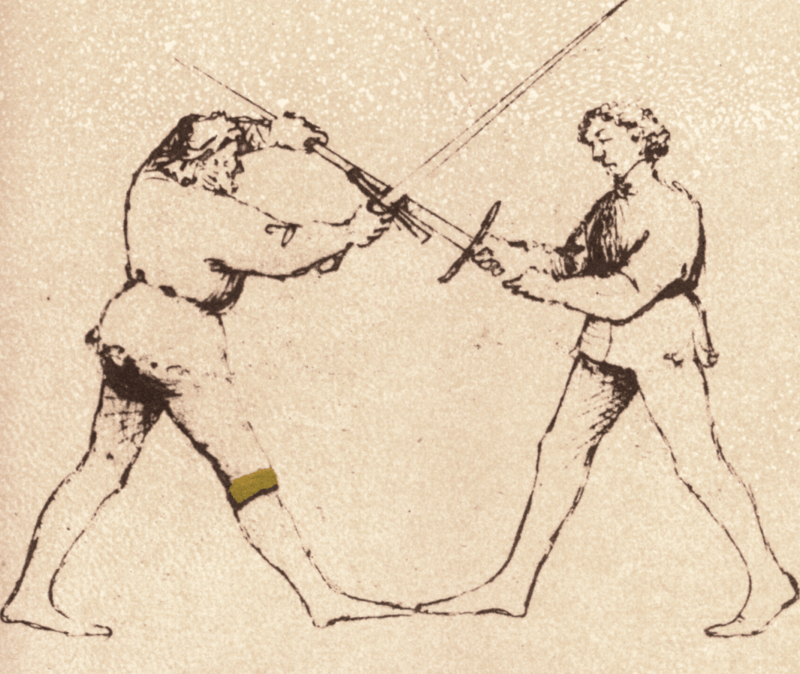

3. Proximity – You have to grab the thing that is close to you. In Duello Armizare we practice disarms at different parts of an opponent’s weapon or arm. In this way you’re prepared to control and exploit whatever is closest. Reaching deeper than what’s offered typically loses the moment. Some historical examples of disarms conducted at various points on a blade:

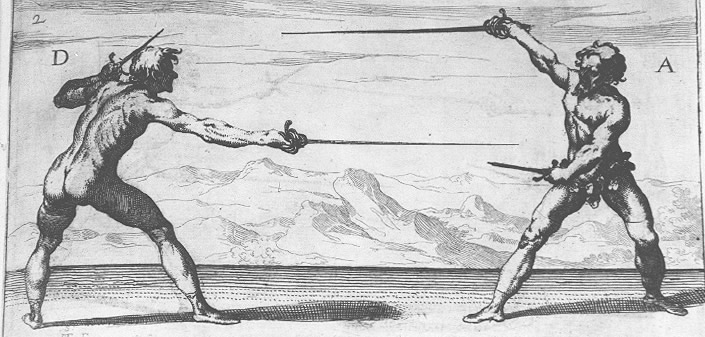

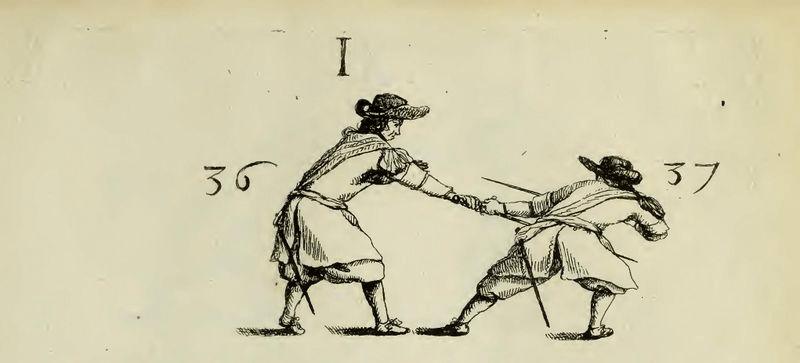

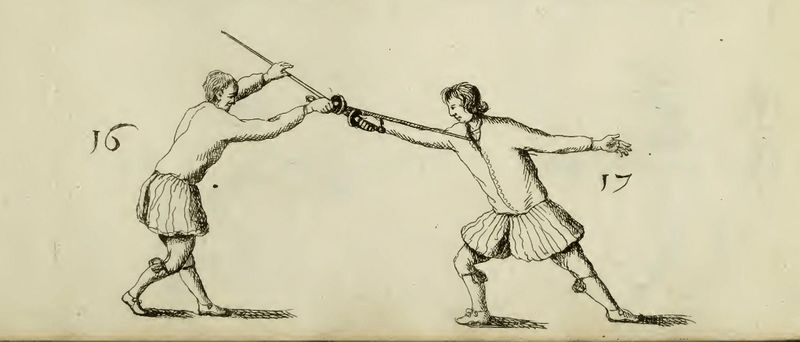

4. Leverage To successfully perform a disarm you need to elongate the levers you’re using against your opponent, shorten those they might use against you, and be in control of the fulcrum. This can be done by catching your opponent in a moment of extension (like at the end of a committed attack), stretching them out, keeping your own arms close to your body, and using your body or weapon as the fulcrum. Here Johannes Bruchius depicts the use of a fighter’s own sword as the fulcrum, keeping his arms tight to his body, and exploiting the lengthened position of his opponent’s lunge:

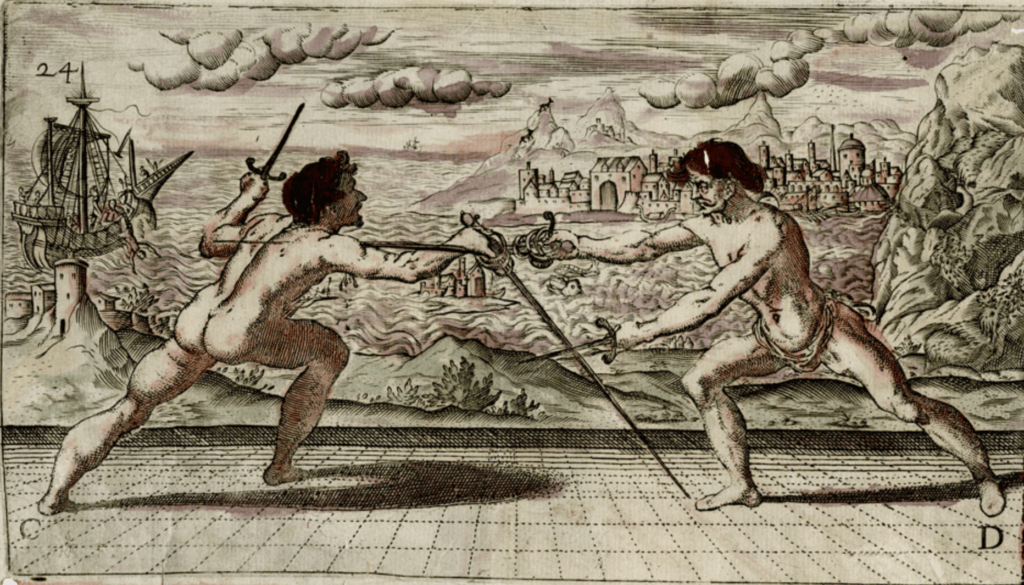

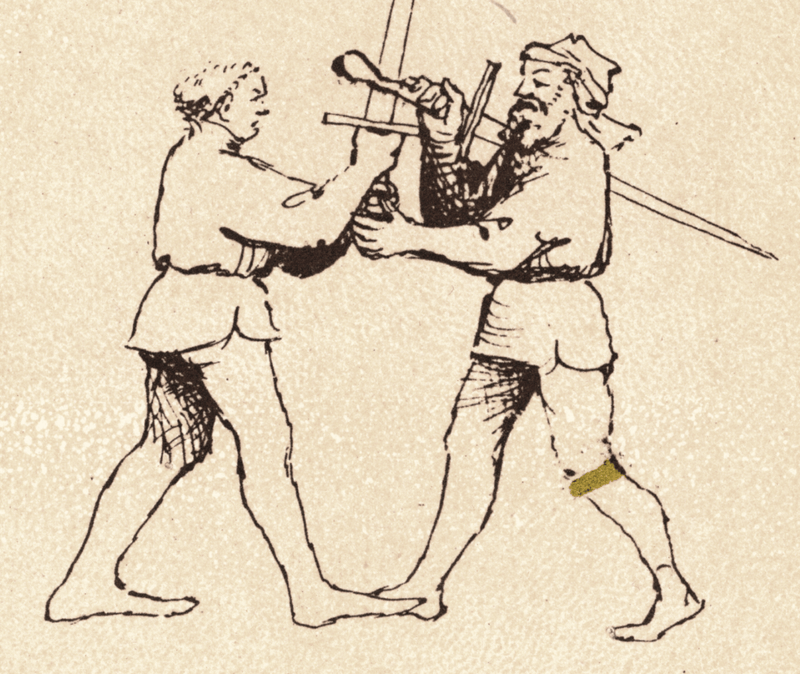

In the following disarm Fiore demonstrates the use of the fighter’s body as the lever in an enveloping “serpentine” disarm:

5. Mechanical weakness Leverage on its own is not enough. You need to ensure that you take a weapon out through the place where the fingers in the grip meet the palm. This involves both turning the opponent’s hand so that this weak point is exposed and levering the weapon out in the right direction. This means upward when the opponent is palm-up, downward when they’re palm-down, and laterally when they’re in a neutral position.

When conducted correctly a disarm should feel effortless and surprising. Strength is never a good tool to rely on. If you’re using strength then when you encounter resistance you’re apt to put yourself into a position of mutual struggle and greater risk. You’ll also be more vulnerable to someone who is simply stronger than you.

In these disarms you’ll see me capture control of the opponent’s weapon at various distances. In each case he seeks to turn the hand to expose the fingers and then uses leverage to bring the weapon effortlessly from the grasp.

Ow! My Hand!

As you’ll see in my video there are many moments where I am grabbing my partner’s sword in my hand. This is both functional and historical.

Though swords are sharp, to cut they either need to impact a target with acceleration (cleaving) or be drawn with pressure along a target (slicing). You can safely grasp a weapon if you:

- Grab it when it is not in motion.

- Apply pressure to the flat instead of the edge — ideally also bending the blade slightly.

- Grip firmly so the weapon cannot be slid through the hand.

- Grab closer to the hilt where the blade is both more substantial (more to get a grip on) and typically less sharp.

Typically you would also be wearing a glove. In demonstration I usually do not so observers can more clearly see the motions of my hands and fingers.

Some Tips on Safety and Training

As you step into exploring disarms I recommend that you start your explorations at slow speeds and with minimal force. A good disarm should overcome even the greatest resistance with minimal effort.

If you’re practicing with complex hilted swords (like rapier and some sideswords) I recommend not putting your finger over the cross bar or ricasso and simply gripping the handle. This will minimize the potential for your hand to be trapped by your hilt during a disarm. At higher speeds this trapping will not stop the disarm from succeeding but you might have a finger broken in the process. I direct my students to always remove that risk from practice.

Build your speed and the opponent’s resistance gradually and with control. A sword can eject from an opponent’s hands in surprising ways, and sometimes flies in directions you never anticipated. A disarm is far less glamorous when you disarm their hilt into your own nose! And take care of all surrounding furniture, flooring, and of course nearby students.

Master the Disarming Skill

A well conducted disarm is a thing to behold and I want to help you start wowing your sparring partners as soon as possible. Duello Armizare has a systemized and effective approach for learning disarms quickly and safely and I’d like to share it with you.

You can develop the skill of fast and effective disarms with our DuelloTV course on Disarms and Dagger strikes. Though this course focuses on the rapier the skills are relevant to all one-handed and most two-handed sword scenarios. Start the Disarms and Dagger Strikes course today.

In this course I bring you through disarms that initiate both from a position of control (true-fight disarms) and those where you have yielded to an opponent’s attack (adaptive disarms). You’ll also learn how to counter disarms with grapples and disarms of your own.

As a bonus I also teach you how to use an offhand dagger both as a part of disarms and for fighting in close.

Subscribe now to access Disarms and Dagger strikes and over 400 more lessons.

Happy disarming and remember to keep yourself and your training partners safe!