Conversations on Binding at the Sword

Not long ago I had a conversation (online of course—who talks on the phone or in person anymore?) with my student Xian from Halifax. He asked a question about the nature of longsword fencing as it is often seen now in tournaments and in many videos online: “Why don’t we see more play at the bind?”

For those who are unfamiliar with the term, “the bind” is when two swords cross and engage in some level of pressure (pushing toward each other). When swords are binding, typically the point is quite threatening to you (if you pull your sword away you could be easily struck by a thrust). Play at the bind is a significant part of techniques shown in historical manuals, so Xian’s is a particularly interesting question.

Here’s our brief conversation (with some additional thoughts in brackets):

Devon: I think resistance to the bind comes from a few different places. One might be that we have some modern cultural mythology, primarily from movies, that has told us what a sword fight should look like. Big, visible, powerful strikes that tell a good story.

(Most people when they come in to sword fighting already have an image of the ‘character’ they want to become through doing it. These characters are often from media or at least heavily influenced by our watching of media, and thus bring a sword fighting aesthetic with them that is rarely based in any way on history.)

Devon: Another is that working from the bind is difficult and takes practice and guidance. If you practice in an environment that is point-scoring oriented, and your training comes more from what is immediately successful to score points, it might lead you away from working in the bind as its hard to get immediate payoff there.

(This is particularly true if you are training in a sparring-oriented club where there is little formal teaching and most regular get togethers are based on fighting and figuring out for yourself “what works”. Getting good in the bind takes hundreds, or thousands, of hours of work, typically much of that failing at doing it well!)

Devon: Also, a sharp-sword environment changes one’s attitude. You’re less likely to want to leave control of the weapon. Contrast that to when getting hit is less significant. Seeking to “strike without being struck” is very important when being struck is high consequence (injury or death!). Where’s seeking only to hit first, best, and most often, can be a fruitful strategy when the environment rewards *hitting* more than not being hit.

(This is perhaps at its most extreme in some of the one-on-one bouts in the Battle of Nations and Armoured Combat League where the winner is the person who has made the most hits within a certain time limit. Here you’ll see matches where there is not a single parry even attempted as it is more successful to simply strike as fast as possible to rack up the higher score.)

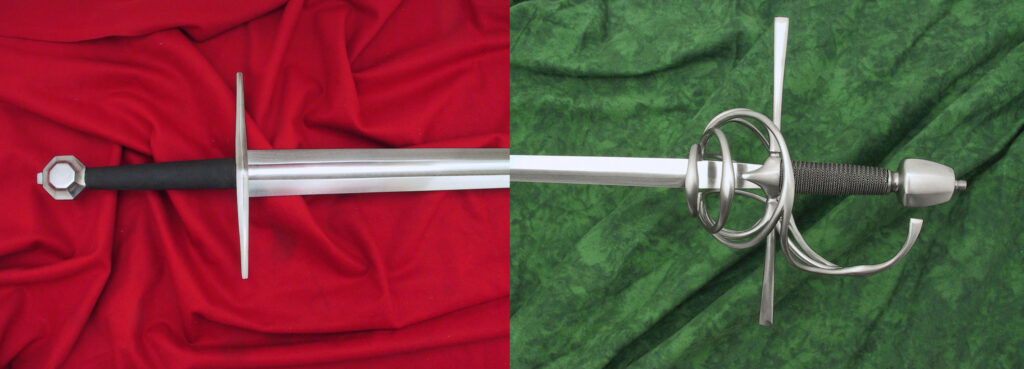

Devon: Sharp swords also bind differently than dull ones do. The binding is very palpable and sticky. It’s a bit harder to leave contact so easily because of this. There’s also an even greater advantage and ability to manipulate the course of your opponent’s weapon through this sharp edge connection.

Xian: So then what we have that is rampant now, is what the masters described as play fighters or free fighters?

Devon: To a degree. But in most of those times—especially the middle ages—the practitioners were never very divorced from the real thing. That would always influence your training.

(If you are applying your skill not just in tournaments but also in self-defence, duels, and on the battlefield, there is always an impetus for your core training to be oriented toward “real” fighting. This means you are going to see more “real” techniques in tournaments that take place in that time. We actually see a shift in the nature of tournaments, and technique, toward a more sporting oriented approach as swordplay and jousting skills lose their battlefield relevance.)

Devon: I also find that even in a play-fighting environment, working in the bind and knowing how to do it well is a supremely powerful tool. It just takes time to learn how to do it well.

Devon: It’s difficult to learn how to play in the bind if you don’t have a training environment where that’s encouraged. So if at your place of practice you spend 90 percent of your time avoiding the bind and only 10 percent training in it (especially in higher/faster level tactical or combative training) then you’ll have a hard time being useful with binding, or at all comfortable with it when it happens.

For interest I’m including a video here of myself and my student Matheus Olmedo doing our martial challenge with sharps at the Vancouver Martial Challenge in 2016. It’s notable to see how the sharp swords stick to one another as we bind. Note we are fencing at a controlled speed and without conclusion.

Responses