Is There a Link Between Ballet and Fencing?

I have long heard that ballet has its origins in historical fencing. It’s a romantic idea and as someone who both teaches martial arts and dance (though not ballet) I certainly find tons of parallels in how they are both taught and practiced.

The positions of modern ballet certainly bare some resemblance to classical and historical fencing positions, though turned out to an extreme.

The connections are often cited to either originate in Italy with ballet evolving as a dance interpretation of swordplay of the 15th or 16th centuries—Catherine de Medici, a patron of the arts, is cited as the cultural transport of ballet (coming from the Italian word ballo) to France when she married Henry II in 1533, to later become Queen of France in 1547.

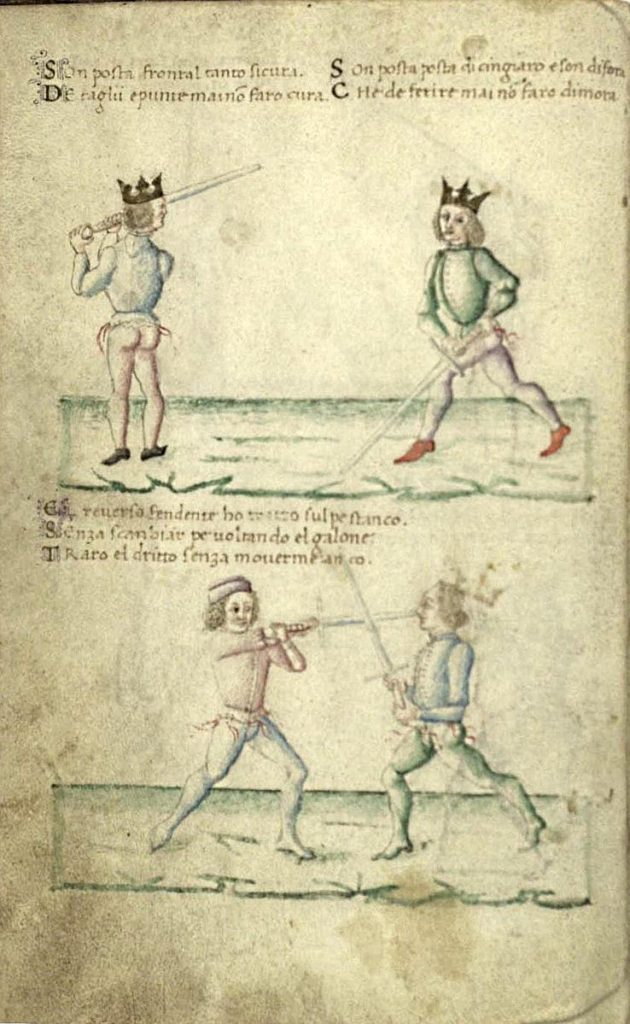

Images from the 1470 Manual of Phillipo Vadi of Italy

Note the turned out feet in the gathered positions (upper left).

The upper left in this second image looks very much like ballet’s first or second position in their most turned out sense.

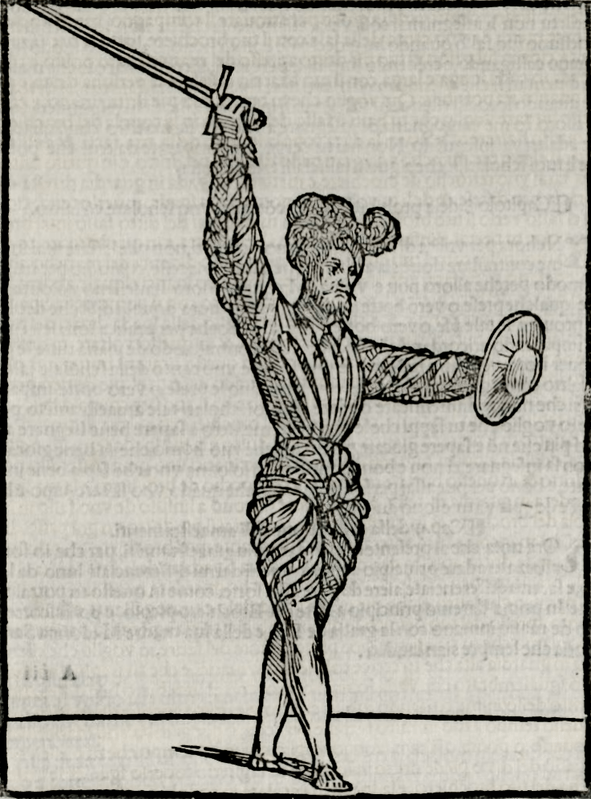

Image from the 1536 Manual of Achille Marozzo

Here you also see some of the long lines and turnout represented in ballet.

The French Connection

The other theory is that Louis XIV of France (reigned from 1643–1715), an avid dancer and student of fencing, brought in aspects of fencing footwork and exercise into his own practice of dance and into the form of ballet that we know today.

Image from Philibert de la Touche 1670

Les Vrays principes de l’espée seule (The True Principles of the Sword Alone)

Image from Jean Labat 16961

L’Art en fait d’Armes ou de l’épée seule (The Art of Arms or the Sword Alone)

This video presentation by ballet mistress Ursula Hageli by the Royal Opera House is one of those rare situations where the Youtube comments are more informative than the content in the video itself (and are actually safe for work!). It’s worth a watch and read.

A couple highlights from the comment thread:

From Ken Mondschein (a well known historical fencing researcher)

With all respect due to Mme. Hageli, I’ve been studying the history of fencing (and practicing the art) for some time, and I’m afraid I don’t know about any boots—the feet are turned out because it is more biomechanically efficient for the lunge. There is evidence for specialized fencing shoes, but nothing I am aware of for fencing in boots. Other quibbles: The dancers’ movement is not correct for baroque fencing, but rather looks like modern ballet. Further, though they have beautiful costumes, they are not using the proper weapon for the court of Louis XIV, but rather cheap reproductions of 19th century sabres. While I am not an expert on the history of dancing, and would not presume to comment on that subject, I am somewhat knowledgeable about the history of fencing.

From DarkDancer06 (this comment is in line with other research I’ve done)

Contrary to popular belief, ballet did not begin at the court of King Louis XIV, nor did it begin in 17th-century France; it actually began 200 years earlier in 15th-century Italy, where it originated from the social dancing of the aristocratic society. It was the Italian Queen of France, Catherine de’ Medici who introduced ballet to the French court after she married King Henry II of France. Queen Catherine de’ Medici was a patron of the arts because she brought with her many traditions and entertainment cultures from her native Italy and it was from these traditions that the Ballet de cour (Court ballet) was developed, with what has been considered the very first ballet de cour – “Le Balet comique de la Royne” – premièring in 1581 during the reign of Catherine’s son, King Henry III. The ballet de cour was performed during the reigns of succeeding kings, including Henry IV and Louis XIII, usually at royal events like weddings and festivals, but it was during Louis XIV’s reign that the art form reached its climax and he founded the first official ballet school – the Academie Royale de Danse in 1660. Also, I haven’t read anything about fencing ever having an influence on ballet’s origins, which I think is very unlikely since ballet developed from Italian social dancing, not sport practised in the Royal French court. If it did have any influence, then I’m yet to find a source that confirms this.

I agree with Ken’s point regarding the biomechanical advantages of being turned out. Beyond aiding in engaging the heel, and thus the gluteal muscles when pressing off the floor in a lunge, a turned-out foot also facilitates keeping one side presented while you pass with the feet. Conversely, if you walk naturally then the lead shoulder changes (thus pulling the weapon away from the opponent).

Something the other commenter seems unaware of is that there was a rich tradition of swordplay in Italy that was well underway in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries (per the images above). That tradition influenced the later fencing of Louis’ court (there are vast connections between Italian fencing and fencing traditions throughout the continent). So the possibilities of the movements of swordplay coming with ballet in its transit to France or being added later are both present.

A Tenuous Connection

So far in the research that I have done it’s difficult to affirmatively say that martial footwork is intentionally present in ballet. In fact, there are many reasons that these parallels could exist:

- Similar biomechanical aims including generating power from the floor, balancing the body in long lines, etc. Matching aims mean matching positions. Looking across the world, for example, postures in medieval and renaissance swordplay match many postures in contemporary Chinese martial arts without there being a technical link.

- Social influences. Swordplay, particularly in the noble realm, is influenced by social physical aesthetics. In different times certain ways of holding your body were considered more noble, stronger, or more manly. These cultural preferences influenced the way people moved and physically presented themselves across contemporary arts and in life in general.

- Material culture. The clothing, footwear, and spaces of fencing and dancing intersect and put shared influences on these arts and noble life in general. There are many ways this can lead to parallels in physical aesthetics.

Perhaps someone reading this will have more to share. I’m certainly interested to find more on those instructors from the middle ages and renaissance who taught both fencing and dance.

What I can say is that there is a lot to learn from dancing, particularly highly technical and physical dances like ballet. I have received my most thorough lessons on efficiency of motion, power generation, and structural stability from dance instructors.

From a research perspective there is also much to be said for understanding the contemporary dances to the swordplay of any era, as well as the other aspects of the culture that surround those arts. Most historical practitioners of martial arts would have also studied dance. Fencing and dancing were both noble physical pursuits and an important part of courtly life.

Swordplay, like dance, existed within a broader context and it’s difficult to fully understand the technical and pedagogical choices that its early instructors made without understanding the broader forces that influenced them.

Thanks for reading and please feel free to share any additional information you might have in the comments.

Devon

Adriano here (aka Adrien, Adrian)

Rapier FUNdamentalist & AMATeur Ballerino

(- in Italian the fem/masc forms of ‘dancer’ end in -a/-o respectively)

(- in France, the dance genre that WE call ‘ballet’ THEY call ‘danse classique’)

Neat topic! I will delve into my ballet library.

Meanwhile, here are a couple of interesting angles to consider…

https://www.facebook.com/lovelifedance/videos/1955951151323552/

https://m.facebook.com/HistoricalPerformanceEnsemble/

1. The video referenced is understandably inauthentic to me: property masters in ballet (and Hollywood) are not necessarily well versed in portraying historical weaponry and form accuracy, though ‘results may vary’ in the entertainment sphere. Asian martial arts and Chinese opera entertainments: same (stylized, artistic licence, choreographed, etc.) Re-enacting / revivalist / preservationist enthusiasts would be more true to form I would think, whether Civil Warriors, cosplay Star Warriors, or what have you.

2. I too believe that psycho-social mannerisms might be the common thread that ties period personal and group behavior, language, practices and customs (including fashion) all together. This exists even today (e.g. hip hop culture). (An argument could be made for women dancing on toe point sharing an aspect with historical Chinese female foot binding customs e.g. to please men, the male gaze, fetishistic eroticism). In the west we have complicated notions of ‘honour’ whereas in the east we have ‘face’… so two manifestations of complex social obligations and displays.

3. Ballet traditionally is binary. More to follow.