Parry Like a Boss

Parries often get a bad rap. Yet it’s mostly because people suck at them. They chase, flail with their arms, or simply try to use force instead of geometry to win. In today’s post I am going to teach you how to make a strong and efficient parry that will allow you to defeat the most powerful of attacks and counter-attack like a wizard, even if you’re in a different weight class than your opponents.

First, Some Terminology

A parry (in Duello terminology) is a dedicated action designed to stop a blow by interposing your sword in front of the path of your opponent’s oncoming blade. For example, if your opponent is making a cut from their right shoulder you could place your sword in its path by making your own cut from the right side that meets it before it hits you, or you could place your sword on the left side of your body to block the direct path. Both of these would be types of parries.

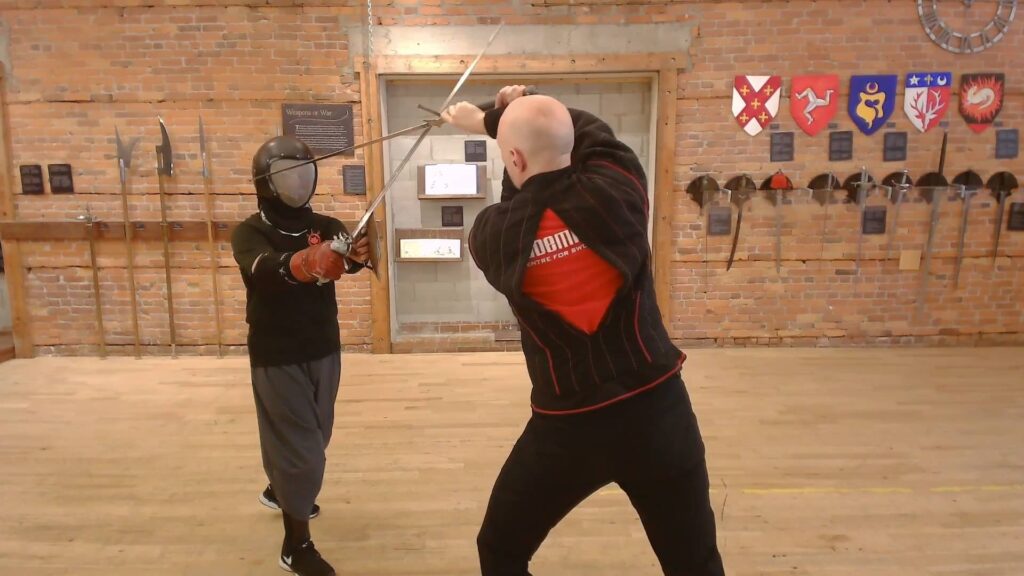

Here’s a quick summary and demonstration of these two ideas:

A parry is one of five classes of defense, the others being:

- deflection – meeting behind the opponent’s blow.

- collection – guiding the blow into your sword’s hilt.

- counter-cut – a parry that simultaneously strikes with your edge.

- counter-thrust – a collection that simultaneously strikes with your point.

Now let’s get into the weeds on parries.

Crossing Parries and Wall Parries

There are two distinct ways that you might perform a parry.

First is to essentially cut into the opponent’s attack with a cut of your own that either has superior geometry or force to that of the oncoming attack—a crossing parry.

Second is to place your sword in the path of the oncoming attack so that it creates a wall that is structurally formed to sustain the force of the blow (or in some cases yield to that force in a way that guides the opponent’s attack past your body)—a wall parry.

Both types of parry can be done well provided you know how to form them correctly and when to employ them tactically.

Today I’m going to focus on crossing parries as they tend to require less structural strength and more immediately present a threat and fast counter-attack.

Correctly Performing a Crossing Parry

A crossing parry succeeds by either expelling the opponent’s sword from the centre or by placing you in a bind with the three advantages (crossing, leverage, and true edge) over your opponent’s sword. Both outcomes leave you in a position where you have a time advantage and are free to counter-strike with control and safety.

There are three core ways you might cut into an oncoming attack:

- With a full turn / full cut (tutta volta). This is often called a breaking parry and is done by making a cut that passes through the oncoming attack and continues its motion into a full circle that allows for a returning counter-attack to the opponent. A lot of downward force is imparted into the opponent’s blade.

- With a half turn / half cut (mezza volta). Here your cut meets the oncoming blow in the centre and arrests itself there with your point remaining online. The opponent’s blade is either expelled (though not as far as with a full cut) or binds, but you are in a position of advantage. This parry imparts a good deal of lateral force into the opponent’s blow.

- With a stable turn (volta stabile). This type of parry is typically done when your weapon is already in front of you. As the oncoming attack descends you “cut” into the attack to gain the advantages by simply directing your point and turning your edge.

Here I give a quick summary and demonstration of these three turns as applied to parries:

Getting the Geometry Right

Whether you intend to expel your opponent’s sword out of the centre or stop it dead, good crossing parries are about geometry, not force. To overcome even the most powerful blow you want to do a few things:

- Cross the oncoming attack with your parry in a way that places you over their weapon. This will tend to meet the opponent in a way that is mechanically weak for them and will make it difficult for them to cut back into your parry to defeat it or bind with it.

- Meet with your middle sword (mezza spada). The middle sword strikes a good balance between velocity and leverage. It also keeps the opponent away from your hands (an easy deviation for an opponent to make in targeting).

- Meet the opponent’s middle sword. When you meet the opponent’s middle sword you will have sufficient leverage to be powerful (especially when combined with the angle you created in step 1) while also making it difficult for your opponent to get to a new line (increased penetration). The time it takes for them to get around your parry and to a new line (by going over your point or under your hilt and hands) gives you the time to successfully counter-attack or increase control.

- Orient your centre to the crossing. By changing your body’s facing so your centre (most easily understood as your breastbone or naval) aims toward the crossing, you are aligning your strength toward the place where you’re working and away from your opponent’s centre. In this way you have more leverage over the crossing, which makes it easier for you to find and stay in control even against a strong opponent.

- Give yourself time. Do this by ensuring your parry motion is shorter than your opponent’s attack, or by stepping back (or doing both of those things). Your parry needs to win advantage over the opponent’s attack before your opponent hits you or controls the centre. Keep in mind that when you are parrying you are by definition starting later than the opponent so you have some catching up to do. Stepping away from their attack buys you that time and space.

This quick lesson shows these five ideas in action:

What About Hitting It Hard?

If you do not create the appropriate angle against a blow, another way you can defeat it is to hit it really hard. The reasons I do not advocate this approach as a primary strategy are:

- You just might not be able to hit it hard enough (because you don’t have time to generate sufficient velocity or lack the strength or mass to match your opponent).

- Your attempt at a smashing parry might leave you grossly out of position if your opponent deceives you and changes line. You then won’t have any help in stopping your own sword’s momentum.

Creating advantage in a crossing parry is better because you’re using leverage instead of strength, channelling your opponent’s force toward your centre instead of your arms. You’re also managing your own momentum so if the opponent deceives you you’re less likely to whiff on the parry and be caught out of position.

Defeating a Poorly Framed Parry

The main error I look for is an opponent who makes parries by pushing their sword to the right or left side of their body in a vertical wall. This wall might seem strong. It does afterall create a sense of both low and high protection. Yet its weakness is in how easily the angle can be collapsed by striking with firmness and precision into the weak of the sword.

By throwing a blow and deviating strongly into the opponent’s weak you can collapse the parry and strike through to a target behind it. Even if the opponent has a fast yield, you can make the opponent yield when you want and then exploit the motion of their rotation.

Defeating Wide Parries

If your opponent is parrying forcefully or more broadly then make a feint to draw a wide parry (if you are not there to help your partner stop their sword, they’ll tend to go wider). Then instead of cutting to the opponent, after your feint, cut into their sword following the rules above to gain strong advantage over their position. This will interrupt their attempt to strike or parry a second time. In the moment of their surprise, use your control and superior position to strike them.

Why Parry At All? Shouldn’t All Defenses Be Attacks?

Counter-cutting and counter-thrusting are indeed excellent ways to defend yourself and recapture the initiative. There is a risk to a dedicated parry that you could find yourself caught in a continual trap of parrying one attack after another, or being deceived by a feint.

The reality is that counter-cuts and counter-thrusts are difficult to pull off and have greater risks. Modern tournaments are full of double hits, largely because so many people have the plan of making some kind of perfect single time counter-attack and yet utterly fail to sufficiently cover themselves.

Learning to make effective parries first tends to make the defensive aspects of your counter-cuts and counter-thrusts far better. And, even if you’re great at these single time counter-attacks you are going to find yourself parrying once in a while, whether you want to or not, so it behooves you to get darn good at it. The goal after all is to not be struck—solidify your defensive game and create great moments for attacks that can’t fail.

Have some other ideas on parries? Something here not make sense to you? Feel free to shoot me a note in the comments. I’m always looking for an excuse to learn and share more.

Happy parrying everyone!

Devon

Responses