The Three Defensive Principles, A Cross Martial Approach

While doing some research for another article I came across this video on the Funker Tactical youtube channel that includes some advice from a Vegas police officer about close quarters covering and entry.

There is a lot of merit to his approach and it shares a lot of commonality to some traditional boxing forms within the Italian tradition we teach. The arms wrapped around the head bear strong resemblance to forms of Boar’s Tooth used in some unarmed situations. Now I don’t agree with his comment that boxers and MMA fighters don’t block. There’s tons of blocking, and counter striking through blocks. You don’t have to do much searching to see this.

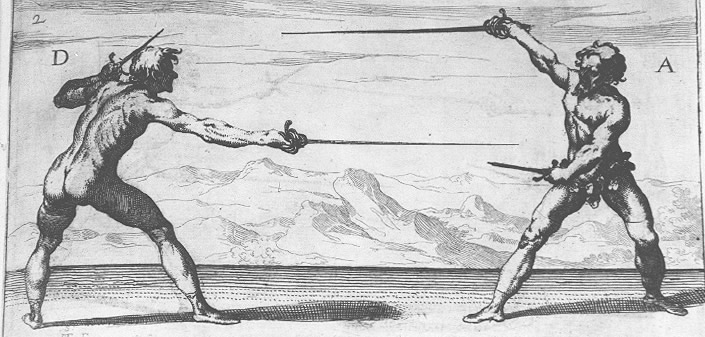

The reality is that sword fights are actually significantly faster than boxing matches due to the accelerative power of leverage on the sword and yet we still see a ton of blocking in swordplay. However, if all tactical options are open and you’re not well trained, blocking is difficult. It’s also much easier to block in a situation where you have a better understanding of the training of your opponents and the consistency of the environment they train for (like can be the case if your martial training focuses on one environment only, like much of HEMA that focuses on tournaments and dueling). Policing must necessarily take into account the chaotic nature of environments and the high variability of opponents. The strategies presented here to me on first blush have a lot of merits.

What I enjoyed most in this video was the highlighting of 3 particular principles he cited as paramount to good defense:

- Distance management

- Cover

- Angle

These happen to be the same principles that we look to in our approach to armed and unarmed fighting. In particular I look to them not just as single avenues upon which you can create defense but as a triumvirate that you look to combine as much as possible.

Distance

Distance is a powerful defensive tool not just because it can put you out of reach of an attack but also because it is one of the best ways to buy yourself time. Forcing your opponent to cover a greater distance gives you time to develop counter-attacks, make effective covers, and seek opportunities to enter.

Through distance we seek to create opportunities to elongate our opponent’s offensive movements and shorten our own defensive or counter-offensive movements (i.e., forcing our opponent to make a long range cut allows us the time to see it develop and counter-cut them with a shorter cut of our own timed at the end of their movement).

Cover

If you misjudge distance or angle it’s essential to have your weapon in between your vital parts and the opponent’s weapon. Through understanding how to properly place and structure covers we can not only protect ourselves but we can also create barriers that the opponent must get around, which buys us more time to make shorter counter-movements.

In our system “cover” includes both parries (aka blocks) as well as placing our weapon in positions that constrain the opponent’s ability to attack (called “stringere”).

Angle

Changing your angle in relation to a given attack or in relation to the opponent in general is a powerful, yet difficult, principle to enact. As you see in the video, he is using angle to change both his tactical relationship (restricting what attacks the opponent can make) and his structural relationship (putting the opponent into a position that is mechanically difficult to work from).

Angle in swordplay is used in these same ways. In relation to an opponent: You might step to their right or left as you make an attack in order to tactically restrict how they can respond to you (they can only attack you easily on one side / they must turn in a given way to face your blow), and to mechanically strike off of an opponent’s centre so they are more easily put off balance or their defense defeated. Or, in relation to an attack: you may turn your centre into an attack in order to defeat it mechanically to parry or to strike through it, or you might step under a blow in order to avoid it while closing distance and changing angle to the opponent.

I think these principles are fairly self-evident and show up in most martial arts that I have practiced. I enjoy seeing them called out explicitly and put to use in similar ways both to how we use them unarmed but in clear parallels to how they are employed in swordplay as well.

Have you seen these principles applied in other martial arts? Feel free to share your insights in the comments.

Devon

Seems to me that all fighting, and perhaps all movement can be understood as a function of “music” and “geometry”, as defined by medieval thought. Where “distance” is referred to as “measure” and where “timing” is referred to as “tempo” we see that swordsmen apparently used the idea of music in a broader sense. Similarly, one can look at “cover” as a function of geometry, as well as the technicalities of the various cuts and thrusts of sword fighting. At the end of the day, whatever the style and tactical preference- it must take form, and it must do so in time and space- hence: geometry and music.

To your question, I see the specific ideas of cover, angle, and distance in all martial arts. Until recently, I had more difficulty understanding this with reference to gunfighting, but the same principles apply there as well. A gunfighter’s basic rules include things like “cover and move”, which is of course a different form of the covering you referred to here, as well as distance. They prefer to take the high-ground, as this gives an angular advantage of sight, if nothing else. When they shoot around barriers, they do so by “cutting the pie”, which is the same idea that La Verdadera Destreza [and others] sought to exploit in cutting “chords”- only in this case applied to projectiles.

Hey Brian, thanks for the response. The shooting connection is quite interesting. One of the attendees in last week’s Instructor Intensive in Vancouver is a pistol and rifle shooter and it was interesting to talk about the similarities he found in various aspects of mechanics and tactical decision making. He made some similar references to you. Just shows that Thibault’s application of the Spanish circle to muskets was hundreds of years ahead of its time. 🙂